Preesall Salt Mining

The turbulent history of salt mining and brine extraction in Preesall is a continuous sequence of warnings ignored with sometimes disastrous results, which has acquired urgent relevance in the light of current proposals for the storage of gas in caverns in the remaining salt deposits below the area and the possibility of gas extraction by 'fracking' not far away.

In 1872 the small Over-Wyre village of Preesall was still a quiet rural backwater, difficult of access and undisturbed since the Civil War, not yet reached by the construction of a railway from Garstang, the nearest market town. A village pub, the Black Bull, presided over by landlord John Parkinson, described as 'the finest sportsman one could hope to meet on a country walk', was patronised by farmers and local tradesmen and frequented by the local squire, Daniel Hope Elletson of Parrox Hall. An idyllic scene, but all this was to change. That year a syndicate of men from Barrow in Furness arrived and, lodging at the Black Bull, began putting down boreholes in a search for iron ore. There was no iron ore to be found, but in a borehole about half a mile south west of Preesall village they discovered a bed of rock salt approximately 400 feet thick 300 feet below ground. They took a sample back to the Black Bull where the landlord's daughter, 17 year old Dorothy Parkinson, dissolved, filtered and boiled it to produce the very first sample of Preesall salt.

It seems they had intended to put down twenty bore holes but, apparently discouraged by their failure to find iron ore, only put down three before leaving. Further action was therefore left open to others and several borings were made during the early 1870s revealing more deposits of salt, a large supply of fresh water and the existence of the Preesall geological fault.

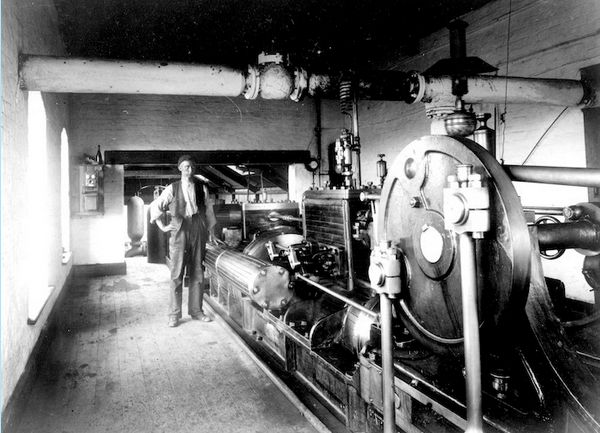

In 1875 the first exploratory shaft was sunk by the Reverend Daniel and his brother in law, Daniel Hope Elletson, who had no doubt been one of the very first to hear about the new discovery. The 8 foot diameter shaft, lined with brickwork, encountered the top of the rock salt at a depth of 309 feet and continued down to 525 feet without reaching the bottom.Commercial interests then took over and events took on a momentum of their own. In 1883 the Fleetwood Salt Company was established to exploit the salt field and a further shaft was sunk, revealing a rocksalt bed 340 feet thick. Water was allowed to seep into the rock head and the resulting brine was pumped out by a steam driven engine working 24 hours a day. This was the first time, but by no means the last, that the old rural idyll was to be disturbed.

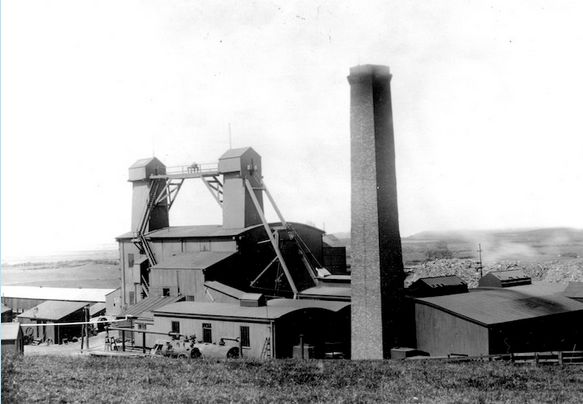

In 1889 the company purchased 22 acres of the Fleetwood saltmarsh at Burn Naze and reclaimed it for the construction of salt works. Railway sidings with a connection to Wyre dock were installed and rates for haulage agreed with the Preston and Wyre Railway Company. Mineral rights over 11,000 acres of land in Preesall, with all necessary wayleaves for pipelines etc., were obtained; drilling of further boreholes was commenced, a brine reservoir was constructed, and pipelines laid to, and across the Wyre to Burn Naze.

The scene was set; in 1890 the Fleetwood Salt Company was taken over by the United Alkali Company, a national organisation, and the level of activity began to gather pace. During the following year the Fleetwood Chronicle reported that many further boreholes were drilled, workers' cottages were constructed, miners began forming a tunnel from the old shaft to enable the quarrying of rock salt, and the works at Burn Naze were expanded to include ammonia soda works and new salt works in addition to the existing thirteen pans in use and seven under construction. By the end of 1891 a reliable pipeline was in operation under the Wyre, salt was being exported from Fleetwood at the rate of six ships a month and the Company had decided to exploit the rocksalt deposits in three ways - Ammonia Soda Works, Salt Works, and also Rocksalt mining.

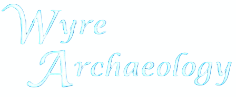

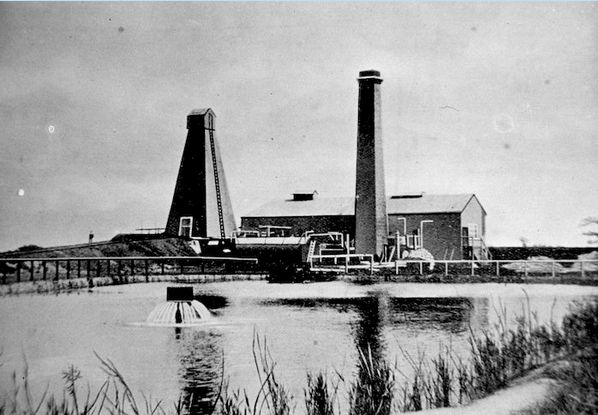

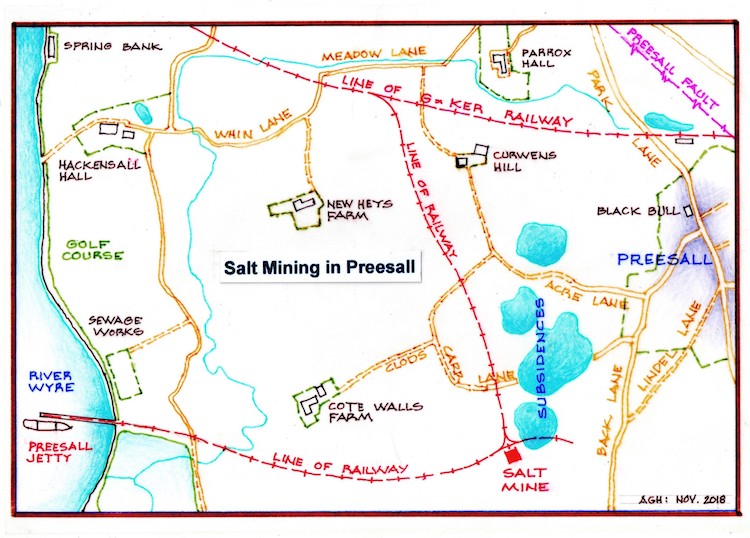

However, the first indications of future problems had already arisen when in January 1890 it was discovered that the rocksalt had dissolved away behind the brickwork of No. 2 shaft leaving it without support. Repairs were carried out, but much more seriously in August 1891 a subsidence over 40 feet deep and over a third of an acre in extent, known as Acre Pit, opened up around No.23 borehole. The Fleetwood Chronicle casually noted that such subsidences were very common in salt districts and that "no doubt the good people of Preesall will in time come to regard the collapse of a field or two with supreme indifference." These were prophetic words.Ignoring this minor incident by 1893 the company had built an Ammonia Soda Works on a new 42 acre site, drilled more boreholes and built a pumping station to force brine to the surface under pressure. The water was supplied by the new Parrox wells, which commenced in 1894, producing 45,000 gallons per hour. Rocksalt mining also commenced in 1893 via two new 450 foot deep shafts, one of which was later extended to 900 feet to form the lower mine. The bottoms of the shafts were blasted out until a cavern was formed, following which salt was obtained by blasting, using black gunpowder bobbins stemmed in and fused with long wheatstraws filled with gunpowder and tipped with a piece of candlewick. Eventually the caverns were between 16 and 40 feet high with pillars of salt 60 feet square left every 105 feet as supports. The mines were lit by electricity except near the rock face where blasting was being carried out, where candles stuck in moist clay were used. Winches powered by compressed air pulled trains of tubs containing rocksalt to the shafts, where they were hoisted to the surface, also serving as lifts for the miners. By 1906 the mine was producing 140,000 tons of rocksalt per annum and steamers up to 1600 tons were being loaded at the new Preesall jetty on the Wyre, served by railway trucks on a rail line direct from the mouth of the mine.

Preesall began to look different and the old rural idyll receded as strange new structures appeared in the countryside, the state of the roads deteriorated, the lanes filled with workmen going to and from the mines, pumping stations and wells, and the sound of 24 hour pumping reverberated across the fields.Preesall hit the national headlines when 'The Times' reported in November 1906 - "A descent into the Preesall pit is an experience of unusual interest. Though the mining operations have only been conducted for a dozen years, the weird, lofty, cavernous vaults formed by the excavation of over a million tons of salt are sufficiently impressive, when illuminated as they are by electricity, to bewilder the spectator who visits them for the first time. " The article continued with a description of the company operations and the statement that "Preesall salt has established itself a very high reputation both in the Australian and South American market..." Future prosperity seemed assured, but all was not well below ground.

Since the formation of Acre Pit gradual subsidence had continued around No. 21 borehole until by 1911 a five acre 'flash' had formed, used by the company as a supply of water without any apparent concern. However, in November 1901 a serious subsidence had also occurred around No. 28 borehole. It was reported that a large plot of land had collapsed entirely, expanding within a month to a hole 100 feet deep by 135 feet in diameter, endangering the works and the chimney. The subsidence continued to expand until eventually stabilising by 1911 into a roughly circular hole 300 feet in diameter.

Despite such clear warnings mining and brine extraction continued apace and in 1912 a mile long branch line was opened from the Garstang & Knott End Railway to the Preesall salt works, providing a direct link to the national rail network. Two special trains ran every day from the works to the G&KER line and in 1918 over 30,000 tons of salt left the works by rail and almost 8000 tons of fuel and materials were brought in. The Salt and Ammonia Soda Works over the river were now requiring more brine, necessitating the sinking of yet more wells in Over Wyre and the erection of water softening plant in Preesall to modify the hardness of the water. It was as if no problems had ever been encountered, but the very worst was yet to come.

The outbreak of war in August 1914 affected the operations of the company in that many men either volunteered or were called up for military service, not all of whom returned, and their jobs were increasingly performed by women both above and below ground. Much of the work was manual, varying from store work to loading trucks with rock salt, using picks and shovels, digging trenches for pipelines and so on, but the women performed their work with skill and good humour and productivity does not seem to have been affected by the war. Operations were intended to continue as normal after the war.However further troubles began in March 1919 when brine was seen to be dripping from the roof of the top mine, a worrying portent since water in a salt mine is extremely dangerous. The problem escalated and within a year 7-8000 gallons per hour were pouring through the roof, originating in No. 2 shaft and entering the mine via No.5 shaft and a tunnel, all of which had to be filled in. At the same time it was noticed that a surface subsidence was spreading towards No. 54 brine well in which the pressure suddenly went off in 1922 when it was found that the lining and uptake tubes had broken off at the rockhead, resulting in the abandonment of the well. Yet again worse was to come.In June 1923 a 12 foot deep hole suddenly appeared adjacent to No. 54, which was being dismantled, and within a week, as the Fleetwood Chronicle reported, it had expanded to the shape of Ô"a wine glass, with a rim of 35 yards in diameter and about 60 feet deep, the stem being formed of a circular shaft about 15 feet round running to a depth not known but probably extending to the brine cavity...." By the 10th August parts of Acre Lane had become unsafe, some farm buildings had been demolished, and the crater was 60 yards in diameter and 60 feet deep.

On 28th September the Chronicle reported that "the huge subsidence which is causing so much interest in the Over Wyre district shows no sign of ceasing." The diameter was now 120 yards, converging on a small hole 75 feet down, beneath which was a cavity up to 400 feet deep into which hundreds of tons of earth, the greater part of an orchard and several farm buildings had all disappeared.

On 5th October under the heading "The cavity that roars" the Chronicle further reported "there come sounds as of the rushing of a subterranean cataract, then a rumble rising to the roar of thunder. The roar has been heard at Pilling four miles away. This great hole, which is visited daily by hundreds of people from near and far, including many geologists, is of such a depth that it could swallow the Blackpool Tower and leave no trace of it."

Alarming events were again reported on 18th January 1924 when "many persons were awakened in the small hours of Sunday morning by bedsteads quivering beneath them. Far from any signs of becoming filled up, the hole seems to be getting bigger and people who had previously thought that the subsidence held no terrors for their own property are now discussing the question of how far it will eventually extend. At night, brilliantly illuminated by huge white and red arc lamps, the scene of the subsidence is an eerie spectacle. Coloured lights make the shiny sides crimson in appearance and the terrifying sounds of titanic earth combats which ascend from indeterminable depths make even the most hardy step back hurriedly."This latest subsidence, known locally as 'Bottomless', eventually stabilised. Westfield farm was demolished, Acres Lane was diverted, and operations continued, virtually as before. In 1926 the United Alkali Company became part of ICI and the emphasis in exporting rock salt changed somewhat from rail to shipping out from the nearby company owned Preesall jetty, but mining and brine pumping continued unabated until the next disaster struck.In June 1930 an area of land about 40 yards square at the 'Flash' subsided and water suddenly poured into the upper mine 450 feet below with "a roar which reverberated through the subterranean caverns" and all the men working on that level had to be evacuated, although work continued on the lower level. Clods Carr Lane, the only access to Cote Walls Farm, had subsided and a new road had to be constructed. Blindly optimistic as ever, the Fleetwood Chronicle reported that all fears of further danger had been dispelled, the water had settled in disused workings and was to be converted into brine, and no further collapses had occurred or were expected.

However, the truth was very different. Salt is deliquescent and will dissolve itself even in damp air, so the ingress of water was a killer blow to the mine. Pumps were installed to pump out the brine but the 20 yard square pillars of salt supporting the roof began to dissolve and as a consequence the mine had to be closed early in 1931. All machinery was removed and the mine was completely flooded within a few months. The Preesall operation was reduced to brine pumping only and the labour force of over 300 men was reduced to only the 20 - 30 required to operate and maintain the brine wells and pumping machinery.

Brine continued to be pumped out of the flooded mine until in 1934 the land above the mine, north east of the shafts, collapsed to form yet another lake known locally as the 'Big Hole' and pushed brine up the two mine shafts high into the air to flood the surrounding fields. Since that time there have been only a few minor subsidences over the early brine wells, the pumping of brine from wells continued, and even more were put down.

In 1956 ICI purchased 20 farms amounting to1550 acres of land in Pilling from the Elletson family in order to secure their water supplies for future production, although some were later sold to the tenants.

By that time all the buildings at the minehead had long been demolished and the jetty and rail links dismantled. The site was left derelict, the two mine shafts being roughly boarded over, insecurely enough to allow teenage boys to drop lumps of brick through the gaps and wonder at the abyss beneath their feet. Brine pumping continued without any noteworthy disasters for many years, through the 1980s, until eventually ICI itself was dismembered and asset stripped, its large landholdings being sold off, enabling the Elletson family to purchase some land in Preesall to add back to the Parrox estate. Maintenance of the brine wells continued, the cavities being filled with a saturated brine solution and closely monitored.

It seemed that the story of Preesall salt was approaching its conclusion and that some semblance of rural calm might return despite the very large increase in population, particularly in the settlement of Knott End, which had barely existed when salt was first discovered.

However, this was not to be; a successor company has purchased large areas of the ICI landholding and, despite evidence of unsuitable geology, environmental damage, potential danger to the local population and massive local opposition, actively proposes, with government approval, to store huge amounts of gas in enormous new caverns to be formed in an area already riddled with literally dozens of old cavities, collapsed mine workings and extensive areas of subsidence, bisected by a geological fault.

As if that is not enough, another company proposes to extract natural gas from the underlying strata of the Fylde by 'fracking'. Their very first attempt, in a borehole several miles away, produced an earthquake which shook Preesall, an event not equalled since the collapse of the 'Bottomless' pit at Westfield in 1923.

Far from now being able to relax the good folk of Preesall once more need to be on the alert amid fears of a return to the disasters and the sound and fury of the past as outside predators circle like vultures over the prospect of rich pickings, although at least we should by now have learnt from our own local history that no safeguards or assurances of protection from harm or damage can ever be believed, whatever their source.

And finally what of 17 year old Dorothy Parkinson, the landlord's daughter who boiled the very first sample of Preesall salt in 1872? She married another John Parkinson and spent her life as a farmer's wife at Hackensall Hall Farm, rearing seven sons and two daughters, eventually dying in 1925, just a few years before the final act in the drama of the salt mine at whose birth she assisted. She played her part in our history and her descendants still populate Preesall and Over Wyre to this day. I am one of them.

Gordon Heald November 2018

My grateful thanks are due to Rosemary Hogarth for permission to use her very extensive and detailed work on the Preesall salt industry without which this account would not have been possible. Opinions expressed are my own.

This article was first published, in two parts, almost simultaneously in:

the Blackpool Gazette (30/11/2018 and 7/12/2018)

and the Lancashire Post (5/12/2018 and 12/12/2018).