"Pool" In The Fylde by R. C. Watson

Attention has often been drawn to the relative isolation of the peninsula of Agmund (also the birthplace of the present writer), which until comparatively recent times has been falling behind, or been severely retarded, in the race of progress and acceptance of new ideas. Nora K. Chadwick wrote "The land route north through Lancashire, though not impossible, as we know from references in Welsh bardic poetry, was at all times a difficult one, ....."(1) Swamp and bog were found in abundance, woodland and scrub were profuse, rivers ran in unhelpful directions and were not easily forded, and the eastern fells served only to exacerbate the area's difficulties. It was also less subject to numerically strong Anglian settlement than other parts of the country. (2) After the Norman conquest, the administrative classes were slow to settle the North West, (3) further hindering the acceptance of new ideas developing further south. It is therefore no surprise to find that the Fylde was and is the repository of ancient custom.

As late as the fourteenth century the district was subject to law enforcement by Serjeantry and not the normal 'hue & cry', and the rural population were paying charges commuted from the cattle and food renders on the same lines as the Welsh; all these were codified in the Book of Iorwerth. (4) From the Mersey to the Clyde, on the lowland farms of the coastal plain, Candlemas loomed large in the lives of the people as rent and ingoing day: the upland farms were usually focussed upon Martinmas, another Celtic quarterday, a custom at variance with the remainder of England. (5)

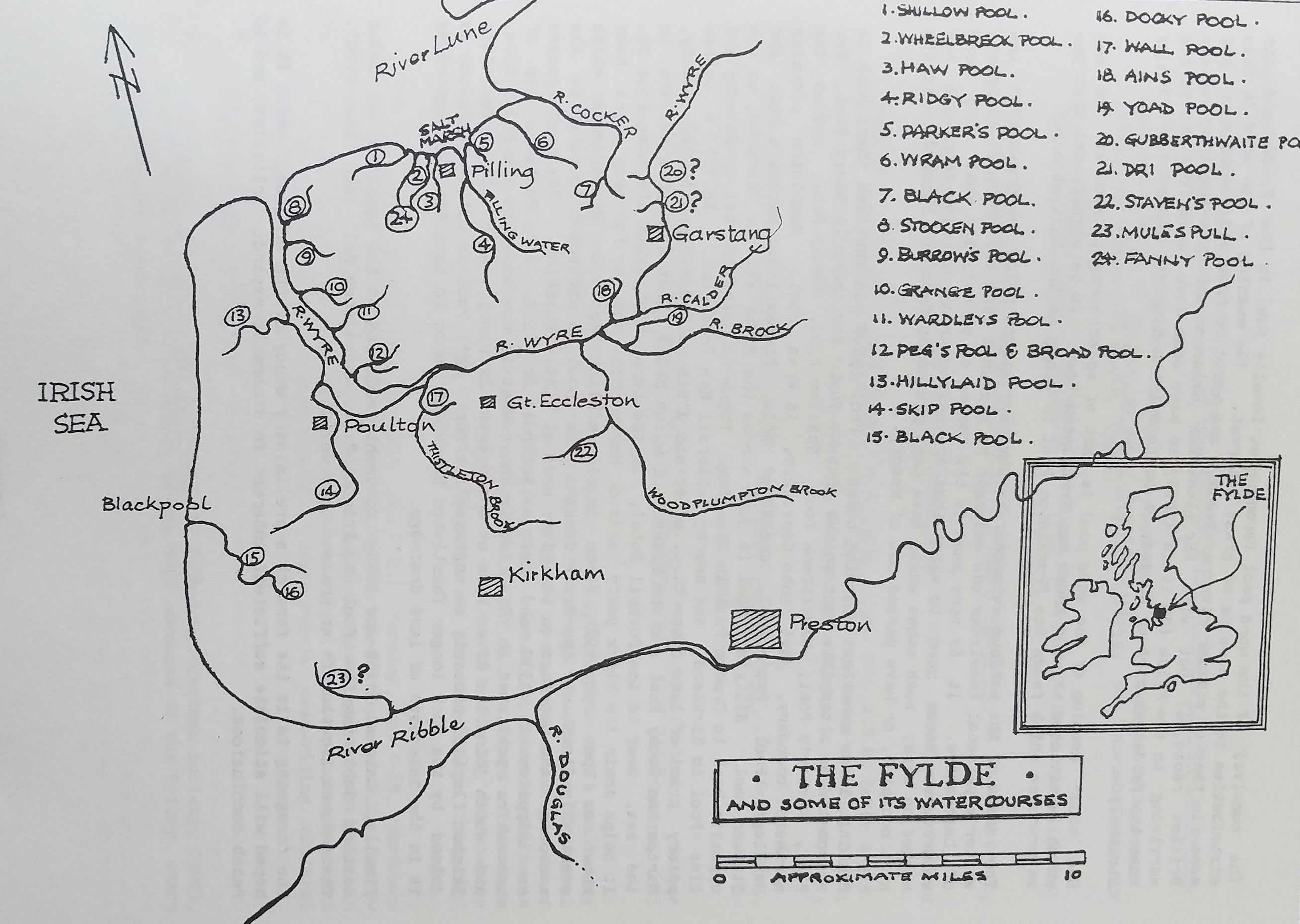

The survival of the word pool (pronounced locally puw) in the Fylde and its distribution in the area is of great interest. The meaning of the word in this area is that of a minor river or brook, and could be from old Germanic or old British roots, (6) but with the plentiful evidence of pre-Anglian customs surviving in the Fylde (7) it is likely to have come down to us from the period when the Fylde was part of Rheged, a north British Kingdom, later succeeded by

Strathclyde.

One other meaning of the word pool is that of an anchorage, such as the one which is situated at, and known as, Freckleton Pool. It is significant that the watercourse which feeds the Freckleton Pool is known as the Pool stream.

The names of the various watercourses that are listed below are drawn from the writer's personal knowledge and enlarged by research into the printed documents of Lancashire. It is very much in the realms of probability that many more watercourse names used to exist that are neither recorded in documents nor marked on maps; such names would have been passed on from one landholder to the next occupant, or have passed out of memory.

Pilling is an excellent starting point. Pool (puw) has survived there both in speech and as a tangible fact to the present day, for there is Ridgy Pool, Haw Pool, Parker's Pool, Wheelbreck Pool, Shillow Pool, Fanny Pool, and on the northern boundary, just into Cockerham, is Wram Pool. Hambleton contains Wardley's Pool, Peg's Pool, and Broad Pool. Preesall has Burrow's Pool and Stocken Pool. Hillylaid Pool is just across the River Wyre in Thornton, on the opposite bank to Grange Pool in Stalmine. There is Staven's Pool in Sowerby and Ains Pool in Kirkland, and nearby Catterall has Yoad Pool. In 1271 a Lytham priory grant of land names ".....a certain ditch called Mulespull."(8) Nearby, Marton has Docky Pool and the Black Pool which still flows through a culvert to the sea, near to the Foxhall Hotel, in the town which takes its name from it. It helps drain the black peaty lands of Marton Moss and has for many years been known as Spen Dyke. (9) There is also a Black Pool in Winmarleigh which eventually flows into the River Cocker. Skippool is now taken to refer to the anchorage and moorings on the River Wyre at Little Thornton. The name appears as Skippoles in 1330 and again as Skippull in 1593, but Saxton's map of Lancashire published in 1577 clearly shows what is now known as the Main Dyke, and which joins the River Wyre at the present Skippool, with the appellation Skippon flu; (10) probably an engraver's error. Wall Pool in Little Eccleston is Joined by the much longer Thistleton Brook and seems to have been subjugated by it in the interests of land drainage.

Finally, between 1189 and 1205, documents relating to the township of Cabus mention Gubberthwaite Pool and Dripool ".....where they fall into the Wyre". Their exact location is at present unknown. (11)

The foregoing is in the form of a preliminary study of the subject, which it is hoped will stimulate sufficient interest in others to expand, criticise, and to reach conclusions.

References

1. ed. Nora K. Chadwick, Celt & Saxon; Studies in the Early British Border, (Cambridge University Press, 1964).

2. "The British Language During the Period of the English

Settlements", Kenneth Jackson in Studies of Early British History, ed. Nora K. Chadwick (Cambridge University Press, 1954).

3. The Norman Conquest of the North, William E. Kapelle, (Croom Helm, London, 1979), see the conclusions.

4. The Serjeants of the Peace in Medieval England and Wales, R. Stewart Brown, (Manchester, 1930).

Lancashire Inquests, Extents, & Feudal Aids, 3 vols., W. Farrer, (Record Society of Lancashire & Cheshire).

Studies of The Field Systems of the British Isles, eds. A.R.H. Baker & R.A. Butlin, (Cambridge University Press, 1973) see 'North Wales', G.R.J. Jones, P.430, quoting 'Llyfr Iorwerth' [The Book of Iorwerth], D. Jenkins, ed., 1960.

5. A General View of Agriculture in the County of Lancaster, J. Holt, 1795.

A History of Leagram, J. Weld, (Chetham Society, 1913).

A General View of the Agriculture of the County of Lincolnshire, Arthur Young, (and for Suffolk, Sussex, Hertfordshire, and Oxfordshire, all published between 1804 and 1813).

6. Oxford English Dictionary, The primary description given is 'A small body of standing or still water, permanent or temporary: chiefly one of natural formation.' The etymological descent is given as a series of variations of the word from Old Low German to Old English. (What, in other words, we in the Fylde know as a 'dub'! For which see the 0.E.D., as a word of Northern or Scottish dialect, or 'Place Names of Lancashire', E. Ekwall, (Manchester University Press, 1922), and 'A Glossary of the Lancashire Dialect,' (Manchester Literary Club, 1875).).

In Northern History, vol. IV, 1969, ed. G.C.F. Forster, pp. 1-28, 'Northern English Society in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries', G.W.S. Barrow makes great play of the fact that amongst the pre-Anglian survivals in Northumbria are the many watercourses named pool. Those he quotes have had 'burn' added to them, which suggests a more recent over-riding cultural influence.

7. Lancashire Inquests, etc., op. cit.

8. In A History of the Parish of Lytham, H. Fishwick, (Chetham Society, 1907), which also contains a reference to the 1460 accounts of the Priory where the spelling is Mulpull.

9. The advent of regional authorities concerned with land drainage has seen the demise of local names for watercourses. The drawing board's technical descriptions describing their function have superceded their names; we have Main Dyke, Main Drain, or Gutter encapsuled for posterity on the o.s. maps. Bispham parish registers for 1602 describe people as of 'de Poole' or of 'de Blackpoole'.

10. Place Names of Lancashire, op. cit., and also note 9 above.

11. The de Hoghton Deeds & Papers, J.H. Lumby, (Record Society of Lancashire &

Cheshire, 1936).