A History of Plover Scarr and Cockersand Lighthouses by Rose Parkinson

In March 1946 at the age of eleven years my husband Robert moved with his parents, Beatrice and Thomas Parkinson (now deceased), to live in the lightkeeper's cottage at Cockersand Abbey three miles from Glasson Dock, south of Lancaster. From 1st January 1946 the Lancaster Port Commissioners had appointed Thomas Parkinson to be the official lighthouse keeper. His wage was to be £2 per week and they were to live rent free.

I had often wondered what this move had meant to them and what it was like to live and work at the lighthouse and I had talked to them about their experiences -- this is their story, which in turn led me to the history of the Lighthouses. The move to the lightkeeper's cottage was delayed from January 1946 until March 1946 to allow essential repairs to be carried out. The cottage required two new ceilings; also most interior walls required replastering and at least one new window was fitted. Even so, the cottage was damp and living conditions were fairly primitive when the family moved in.

Only one room on the ground floor was actually habitable and was used as the kitchen/living room. The other room was little more than a hallway because the entrance to the cottage and to the wooden upper lighthouse and all other rooms was from this one room or hallway, i.e. (1) the entrance to the cottage (2) the door to the lighthouse (3) the door to the kitchen/living room (4) the staircase which led up to the two bedrooms and (5) the pantry door. However, as explained later, there were four further rooms at the base of the wooden lighthouse. Indeed, the cottage is said to have been built by Francis (Frank) Raby, the first lighthouse keeper, when the original accommodation below the wooden lighthouse became too small to house his growing family. The cottage is an odd shaped building; Robert recalls that his corner bedroom overlooking the sea, had no less than eleven corners in it.

The toilet facilities were quite separate, i.e. about 20 yards (metres) from the cottage across the yard, down the garden, originally an earth type, later changed to a bucket type toilet.

There was no mains water supply during the time the Parkinson family lived at the lighthouse cottage between 1946 and 1963. A pump situated by a sink in the corner of the kitchen/living room provided water from a well, so near to the not shore that salt water seeped into it and, this salt-tainted water was suitable to use either for drinking or washing. For drinking water the Parkinson family collected rainwater from the painted roof of an out-building, this they purified in an earthenware chalk filter. A water tank collected rainwater from the gutters of the lighthouse and cottage; this was used for washing and cleaning purposes. This source of water was partially lost when the wooden lighthouse was pulled down in 1954. Later the Commissioners had a concrete water cistern built to collect all available rainwater off the cottage and provide a more efficient water storage system. Water was then piped through the wall from the cistern to the sink. Until 1947, lighting was by means of a paraffin lamp in the kitchen/living room, candles elsewhere. Cooking and baking was done on the kitchen/living room range or on the paraffin oil stove situated in the outside wash-house. Electricity was supplied to the lighthouse and surrounding farms and properties in 1947 and Mrs. Parkinson was then able to have an electric cooker and washing machine in addition to lighting at the cottage.

At the time the electricity cables were being laid lightening struck the cottage. It appeared to travel down the side of the lighthouse and into the kitchen/living room of the cottage and, before going to earth through the water pump it tore a hole in the wall blowing the sink away from the wall, destroying a wireless set (a battery/accumulator type set) and, smashing a ships clock. Fortunately no-one was hurt, although a newspaper report of 31st May, 1947 suggested that a workman engaged jointing electricity cables nearby had a very narrow escape.

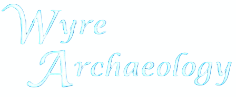

The Wooden Upper Lighthouse

The original doorway which opened straight into the living room of the wooden lighthouse still existed. As stated previously entrance could also be gained through the cottage hallway at the point where the cottage was built onto the lighthouse. Accommodation comprised of four rooms set around a central square from which a square spiral of fifty wooden steps ascended to the lantern room. Although the Parkinsons furnished the living room it was rarely used. One room was furnished as a bedroom where Robert slept when visitors stayed at the cottage, another room became his "playroom", the other room being utilized as a store room. The building was weatherboarded outside and the rooms had plastered walls inside. The tower itself was approximately 54 ft. (18 metres) high. This being an all wooden structure, cooking and heating must have been a problem in the early days before the cottage was built. In the living room of the lighthouse there was a large open fronted cast iron box with a fireplace set into it. The flue ascended through the top of this box, continued through the roof of the room and on alongside the tower of the lighthouse. This chimney was so close to the lighthouse that a fire would not draw satisfactorily despite various cowls and adaptions having been fitted.

The fifty steps which ascended the swaying wooden tower led straight into the square lantern room which had a balcony on three sides. Lighting was by means of two identical paraffin oil lamps; they had a reflector to each lamp and used 1 inch (2.5 cm) flat-wick burners. The lights faced down river directly in line with, but shining over the top of, the lower light. Ships coming up the river had to get the top light shining directly in line i.e. over the top of the lower light in order to guide them up the Lune channel. Normally they would be met by the Pilot at number 6 buoy in the channel, which was the first buoy lower down the channel than the Plover Scar light.

Legend has it that the wooden tower was originally mounted on wheels so that its position could be changed as the channel up the Lune river changed. (I have read of such an arrangement elsewhere) Robert having seen (in 1954 when it was demolished) the substantial stonework beneath the lighthouse to which it was fixed, and having lately seen a copy of the original plans, we can find no evidence to support this theory.

Late in 1953 the upper light was replaced by a steel tower fitted with an electric light. This was a round cylinder about 2 ft. 6 inches (76 cm.) high, 1 ft. (30 cm) in diameter with a small reflector and magnifying glass. Two 12 volt, 12 watt bulbs were used in this apparatus, one to illuminate, the other on stand-by ready to turn over into the lighting position should the first light fail. The ladder had to be climbed in order to re-set the bulb holder to its original position and replace the spent bulb. The new light was still manual in that it had to be switched on and off from a switch situated in the cottage. In the late 1950's the light was however made fully automatic by the installation of a timing mechanism. In February 1954 the old wooden lighthouse which had stood for over 100 years was demolished.

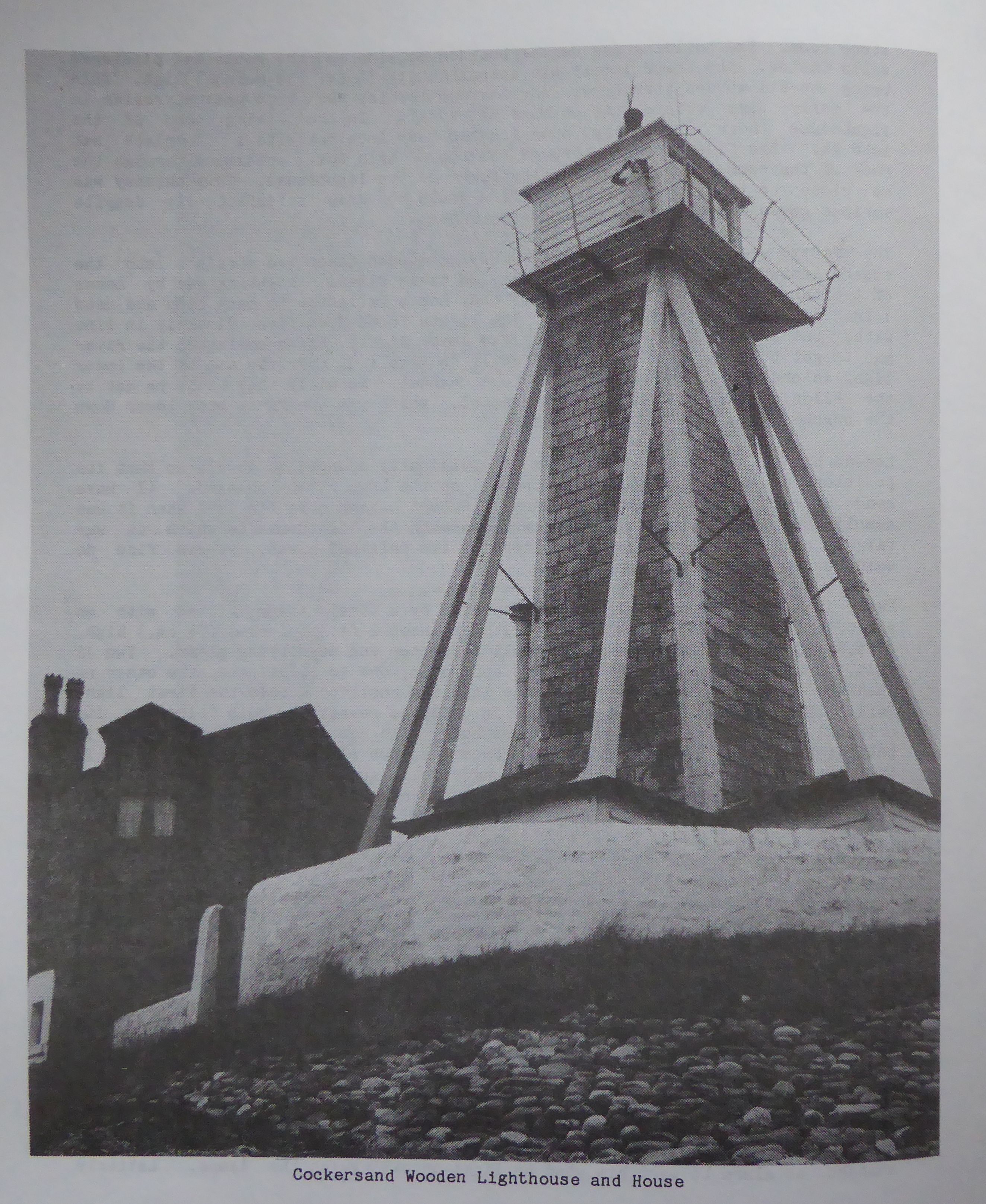

Plover Scar Lighthouse

A wave-swept masonry tower approximately 50 ft. (17 metres) high was built on rocks in the Lune Channel about half a mile from the upper lighthouse. Access was gained at low tide by walking across the sands, along a causeway, past the fishing baulk, to reach and climb a twenty-five rung iron external ladder up the side of the lighthouse, then on to a balcony, in through double storm doors to the keeper's dwelling room. This circular room of about 6 ft. (2 metres) diameter had a small fireplace directly opposite the doorway; wooden seating with seats which lifted to reveal storage places beneath ranged around the available wall space. In earlier years when this lighthouse was manned, the keeper would have had to sleep in this room. A warning system was in existence then by means of a copper float attached to a chain let into the exterior wall of the tower and which led up into the keeper's room. As the tide rose or dropped to a level where the river was either navigable or unnavigable it sounded an alarm to warn him when to light or extinguish the lamps. Latterly all lights were shown during the hours of darkness irrespective of the state and times of the tides. On the right hand side of the doorway of the keeper's room a ten or twelve step vertical ladder ascended through a trapdoor into the lantern room.

Lighting here was also by means of two identical paraffin oil lamps with a reflector to each with 1 inch (2.5 cm) flat-wick burners; these lamps faced down river. There was also a smaller light with a reflector facing up river. This latter light was shown so that ships returning down river could see and avoid the lighthouse.

The reflectors (parabolic) at both lighthouses were made of silvered copper; each reflector had a brass rim and the two lamps were supported on a cast iron column. The glass chimney (approximately 10 inches (25 cm) high) was fitted over the burner by first pushing it through the hole in the top of the reflector. Robert recalls the diameter of the four main reflectors to have been approximately 2 ft. to 2 ft. 6 inches (60 to 76 cm). At this time both lighthouses displayed a steady light.

In 1951 the lighting system was changed to acetylene gas power, a single burner showed a permanently flashing light. The equipment was automatic but had to be checked by the keeper once a month. The gas cylinders which were delivered to the lighthouse by boat at high tide, had to be changed about every six months. The Port Commissioners staff did this job.

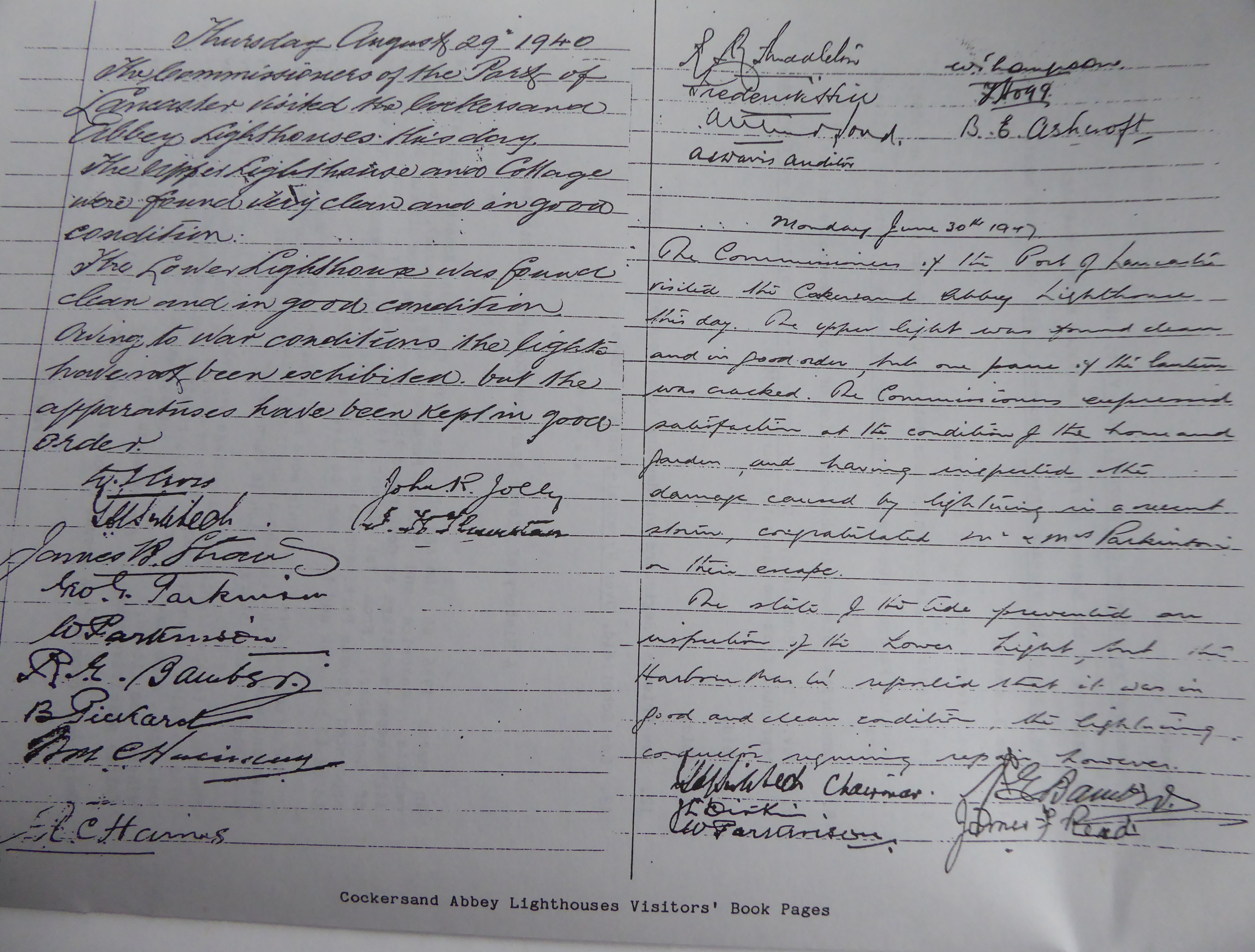

Once a year the Commissioners visited to inspect and report on the conditions at the lighthouses and cottage: each would sign the report in the Visitors Book. When they paid their annual visit on 29th August, 1951 the Visitors Book read "The new acetylene lighting system at Plover Scar was observed to be flashing satisfactorily and the oil burners at the Abbey Light appeared to be in good order".

It will no doubt be appreciated from the description of the keeper's journey to Plover Scar lantern that a twice daily visit was not an easy task in winter, when the wind was blowing hard, waves splashing over the causeway and when the vertical iron ladder was covered with ice.

Lighthouse Duties

Twice a day both the upper (wooden) and lower (masonry) lighthouse lantern rooms had to be visited. In the morning the lamps would be turned off, cleaned, wicks trimmed, paraffin feeder tanks replenished, reflectors polished, windows cleaned and the room made generally clean and tidy. The steps would be climbed once again in the evening in order to light the lamps. About three gallons of paraffin per week was used at each lighthouse.

As stated previously, Mr. Parkinson was appointed lighthouse keeper on 1st January, 1946. It was necessary, however, for Mrs. Parkinson and Robert to assist with duties as the salmon fishing season commenced 1st April and Mr. Parkinson, who held a "heave" or "haaf" net licence would from that date each year be salmon fishing at the same time as the lights needed attention. Mrs. Parkinson would then do the job or alternatively if the tide was at a convenient time Robert would attend to the Plover Scar light before going to school. Be would carry down the two gallon can of paraffin on his back, leave it and return with the other empty can.

Sometimes when Robert went down to the lighthouse Dick Raby would be collecting fish from the fishing baulk nearby and they would have a chat. Afterwards he would often walk back along the riverside to where his father was fishing, carry home in a sack any fish already caught, then take his father a flask of tea and a sandwich (there was nowhere to leave them whilst standing in the sea fishing with a "heave" or "haaf" net): all this before cycling to school 2.5 miles away, for 9.00 a.m. After school before dark he would return to Plover Scar to light the lamp.

If the tide was out in the middle of the day and out in the middle of the night then either Mr. or Mrs. Parkinson would go down to Plover Scar in the middle of the day to put out the light, clean and refill it, then immediately light it again. On those occasions the lights would burn nearly twenty-four hours a day. If the weather was really bad and the tide did not ebb far enough for the light to be reached, then the lamps, at a pinch, would burn for forty-eight hours before running out of paraffin. There had to be a combination of gale force winds and low tides for this to happen. This was because a low tide would not ebb out as far, consequently more water remained in the area of the lighthouse and was held there by the gale force winds, whereas following a high tide there would be a greater ebb and the sea would not remain in the area of the lighthouse.

The Lighthouses in War Time 1939-1945

It is understood that early in the war years the lights were lit only when directed by the harbour master at Glasson Dock. There was no telephone at the lighthouse cottage then, so presumably the harbour master would have to call to see the keeper and instruct him on the arrival or departure of any shipping. Latterly the lights were put out for the duration of the war. Miss Janet Raby continued to live at the cottage and looked after the properties.

Lightkeepers

From their building in 1847 until December 1945 both lighthouses were under the care of the Raby family. Francis (Frank) Raby was appointed keeper in 1847 followed sometime in the late 1870s by Henry Raby: all were assisted from time to time by various other members of the family. Janet Raby assisted by her brother Richard (Dick) Raby was the keeper until 31st December, 1945. Descendents of the Raby family still live in the area i.e. at Glasson Dock. The Parkinson family's involvement with the lighthouses ceased on 31st May, 1963. Nothing is known of the situation since that date except that the lighthouses are now both unmanned and the keeper's cottage is now a private dwelling.

Plover Scar lighthouse has remained capable of withstanding, for over 140 years, the continual pounding of the sea. The Cockersand Abbey wooden lighthouse withstood the wind and storms for over 100 years. more of their history, of the people who planned, designed, built and paid for This inspired me to learn these aids to navigation; this is their history.

The Lighthouses are owned by the Port Commissioners of Lancaster. The Act setting up the Port Commission in 1749 laid down that the Commission was to be elected by the merchants of the Port. The qualification of an elector was that he should own a share of not less than one sixteenth in a Lancaster vessel of at least 50 tons (1).

From 1844 to 1845 negotiations were taking place between the Port Commissioners and Lancaster and Carlisle Railway respecting the crossing of the River Lune below the Old Bridge. In 1845 the Port Commission came to an agreement with the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway to allow their line to cross the river down stream from St. George's Quay, which would thus be made useless for shipping. In compensation, the Railway were to pay £16,500 for depreciated warehouse property and for the building of a new jetty below the railway bridge, and, in addition, agreed to pay £10,000 to be spent under the direction of the Admiralty on the improvements in the navigation of the river.

Lighthouses at the mouth of the river had been discussed and on 1st July, 1845 the River Improvement Committee recommended that two lighthouses should be erected near the perch on Abbey Scar. The admiralty agreed that £2,000 of the £10,000 given by the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway could be used to build two lighthouses.

1846 the plans and specifications submitted to the Commissioners by B. Hartley of Liverpool for the erection of a stone lighthouse on Abbey Scar, and a wooden lighthouse on the shore were approved and tenders requested. John B. Hartley designer of the lighthouses was the son of Jesse Hartley who was Engineer for the Bolton and Manchester Railway and Canal, and Chief Engineer to the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board until 1861. In this latter capacity be designed the lighthouses at Lynas Point in 1835 and at Crosby in 1847. John B. Hartley succeeded his father as Chief Engineer to the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board (2).

The Commissioners accepted the tenders of Mr. Charles Blades 1. dated 28th July, 1846 to erect the wooden lighthouse for the sum of £650 and 2. dated 6th August, 1846 to erect the stone lighthouse for the sum of £1,020.

In the Articles of Agreement made 26th June, 1847 Charles Blades is described as a "House carpenter and joiner" also, it was noted that towards the end of this lengthy agreement he gave an undertaking to finish the stone lighthouse before 9th October, 1847.

Charles Blades had entered into partnership with his friend James Hatch in 1841, and moved to premises in Dalton Square, Lancaster soon afterwards. They dissolved the partnership about three years later but were both able to carry on large scale building and contracting. Blades took part in building Ripley Hospital, the Royal Albert Asylum and the Storey Institute. In 1848 his premises at Dalton Square were burnt down and rebuilt. Later on he commenced importing timber to Glasson Dock where it was stored prior to removal to saw mills, or dispatched. He also had timber stores in Nelson Street and Bulk Road, Lancaster. He owned his own timber ships and in 1860 was elected a Commissioner of the Port of Lancaster. He was Mayor of Lancaster in 1871, 1887 and 1890. His sister Ann Williamson Blades married Sir Thomas Storey. Charles Blades was born 28th February, 1818 and died 17th October, 1893.

An Officer of the Royal Navy advised the Commission as to the position of the lighthouses and, on 10th June, 1847 the foundation stone of the lighthouse on Abbey Scar was laid by John Sharpe Esq., the Mayor of Lancaster, on behalf of the Commissioners.

At a meeting of the Commissioners held on 5th October, 1847, Francis Baby of Overton was appointed lighthouse keeper of the two lighthouses, in the course of erection at the mouth of the river Lune, at a salary of £25 per annum. In the following January the wooden structure was insured against fire, for the sum of £1,000.

In 1850 a report was presented to the Commissioners as to the condition of the stone structure, from which it appeared that the stonework was fractured in several places from the foundation to half its height. The report was presented by the Inspector of Public Works.

Little or nothing appears to have been done about the matter which was raised again in 1868 when the Stevensons were asked to report to the Admiralty on several matters. A plan dated August 1884 showing the "Method of securing Iron Straps to Stone Work" produced by Sharpe Simpson & Co., Engineers & Iron Founders, Phoenix Foundry, Lancaster, appears to indicate that it must have been towards the end of the century before Plover Scar had the extra stone casing, the top of which now forms the existing lower balcony. This balcony did not feature in the original plan which shows an external ladder leading straight up to the doorway and states "Foot Grove (sic) to be rounded out 12 inches x 6 inches. Cast Iron Ladder to be sunk into the Masonry one inch deep on each side".

Robert Stevenson (1772 - 1850) was an outstanding lighthouse engineer of the period from 1801 when British lighthouse services were coming into being on a national basis. Stevenson specialized in seaworks - designing and improving harbours, rivers and lighthouses. His office was in Edinburgh. Three of Stevenson's sons were well-known civil engineers, of whom the youngest, Thomas, was the father of the writer Robert Louis Stevenson (3). It was Messrs. Robert Stevenson & Co. in 1838 who surveyed the river Lune with a view to its improvement, and presented their Report. The Commissioners "had not the means to carry it out". Stevensons also made several surveys of the river between 1847 and 1851 when they took charge of improvements. The Lancaster Guardian of 19th June, 1847 reported that the remaining £8,000 (of the £10,000 given by the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway) was to be spent under the direction of Stevensons. This was evidently the decision of the Admiralty.

The Lighthouse service of England and Wales, the Channel Islands and Gibraltar is under the authority of the Corporation of Trinity House (4). The history of the Corporation is a fascinating subject in itself, which I will not go into here except to say that, although they are owned by the Port Commissioners, Plover Scar and Cockersand lighthouses still come under regular inspection by Trinity House whose sanction must be obtained before any changes are made. One can only wonder what the future may hold for them.

References

1. M.M. Schofield, Outlines of an Economic History of Lancaster.

2. Douglas B. Hague, Rosemary Christie, Lighthouses p. 219.

3. English Lighthouse Tours, Robert Stevenson, ed. D. Alan Stevenson. Biographical note.

4. Patrick Beaver, A History of Lighthouses p. 5.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mr. Morris of the Lancaster Port Commissioners and the staff of Lancaster Library for allowing me access to the Port Commission's documents and for the help given, also for the News items from Lancaster Gazette and Lancaster Guardian deposited at the library. Thanks also to my husband for his help and patience in answering my questions.