Galgate Silk Mills

A Study of the Development of Mill Architecture by R. E. Beeden

Introduction

The development of mill and factory architecture is a subject that, over the past thirty or so years, has been studied and documented to a considerable degree. The patterns of construction that emerged from the last quarter of the Eighteenth century and onwards into the early Twentieth century are ones that illustrate the growing awareness of new techniques and materials. Lancashire, as Owen Ashmore notes in his survey of the county's Industrial Archaeology (1), provides considerable examples of the evolution of textile mill building patterns. The materials used, methods of construction, the operation and development of the mills can be traced via a study of the cotton and other textile mills of the region.

Many of the mills that are still extant are often a conglomeration of building styles having been enlarged or reconstructed over the years. Each additional or rebuilt section probably incorporated newly developed building materials and design features. The older sections of these mills may now be lost within the confines of the more recent additions and it is only by detailed survey work that these earlier parts of a mill might be examined.

In Galgate Silk Mills we have an exception to this rule in that the pattern of developing mill construction can be clearer ascertained from the exterior. The three distinct sections of the Mill reflect, to a large degree, the changes categorised by Ashmore in his delineation of the early and middle stages of textile mill development (2). They also provide a good illustration of the early stages of industrial expansion as outlined by Jennifer Tann (3). The factors involved in this particular business enterprise and its subsequent progress appear to be fairly typical of the textile trades during the past two hundred or so years.

As a silk spinning mill the Galgate enterprise also provides us with an example of how one of the smaller textile trades followed the patterns of development laid down by the cotton and woollen textile trades, even though the first 'factory' in this country is usually shown to be that of silk manufacturer Joha Lombe. The change from a functional and traditional style of building to a purely functional style is clearly shown at Galgate although the change does not appear to have been as rapid nor as complete as in other mills and in other parts of Lancashire and elsewhere.

The Galgate Silk Mills: Their foundation and expansion

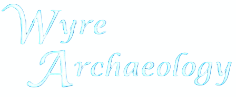

The township of Galgate lies within the parish of Ellel some three and a half miles south of Lancaster on the main A6 road. The Silk Mills are situated or Chapel Lane one of the original routes northward out of the township prior to the construction, in the late 1800s, of the present main road. The River Conder flows through the parish from its source on the Quernmore Pells towards its confluence with the River Lune at Conder Green, some three miles west of Galgate.

It is this river that gave rise to the first industrial development on the site, that of a water-powered corn mill. Water was taken via a weir and millrace from the river half a mile above the mill. This fed the mill-dam (pond) which then provided the necessary head of water to operate two wheels (4) (see Map ).

In 1792 the mill was acquired from the miller, William Bell, by three Lancaster merchants, John Armstrong, James Noble and William Thompson, for the sum of £900. The sale also included the important and essential water rights on the River Conder. The premises were acquired with the sole intention of converting them into a silk-spinning mill (5). In making this purchase the three merchants were following a pattern that had already been adopted by other aspiring textile manufacturers. As Jennifer Tann notes, the existing water mills were easily converted to a different role with practically no external modifications and often with only minor internal changes (6). The alterations that were undertaken were said to have cost £100 (7) and the mill began production on July 27th 1793.

The modest capital outlay may, it is assumed, have been expected to produce substantial returns. Even if the venture had failed a disasterous financial loss would not have been incurred. Failure was not apparent in the minds of the new owners who appear to have planned their venture with considerable business acumen. As a mechanical silk-spinning mill the Galgate establishment would have been one of a very few in the country. It was to use as its raw material the silk waste, from other silk-throwing mills, which was acquired at a very reasonable cost from London and Manchester. From this waste was spun a very high quality yarn. The first Day Book of the mill records that silk waste, bought at the rate of 3s 6d (17.5p) per lb., was sold after spinning at the rate of 17s (85p) per lb. (8). Even allowing for production and labour costs a substantial profit appears to have been made.

In 1830 the company, now controlled by the Armstrong family, undertook the first stage of expansion. This was to be the building of a second mill adjacent to the old corn-mill. Mule-spinning or the short-spinning system had been adapted for use with the waste silk in the original mill and it was because of the introduction of bigger self-acting mules that the new building was erected. Opened in 1832, the second mill required additional power and this was provided by two 10 h.p. beam engines. The engines were housed in a new boiler and engine house which was built on the opposite side of Chapel Lane, power being transmitted via a tunnel under the road into the mills.

Both steam and water power were being utilised when a Government Factory Inspector reported on the Mills in 1835 (9). He reported a total workforce of 102 adults and 50 children with both day and night shifts in operation. The workforce was to increase to over 300 by the end of the century.

Many of the new mill-hands were to find employment in the final extension of the mills which were opened in 1851 on the eastern side of Chapel Lane opposite the earlier premises and alongside the boiler and engine houses. This five storey mill still stands as an imposing example of the success of the company well into the second half of this present century.

The Three Phases of building and their Relationships to National Trends and Developments

Phase One. (see Map)

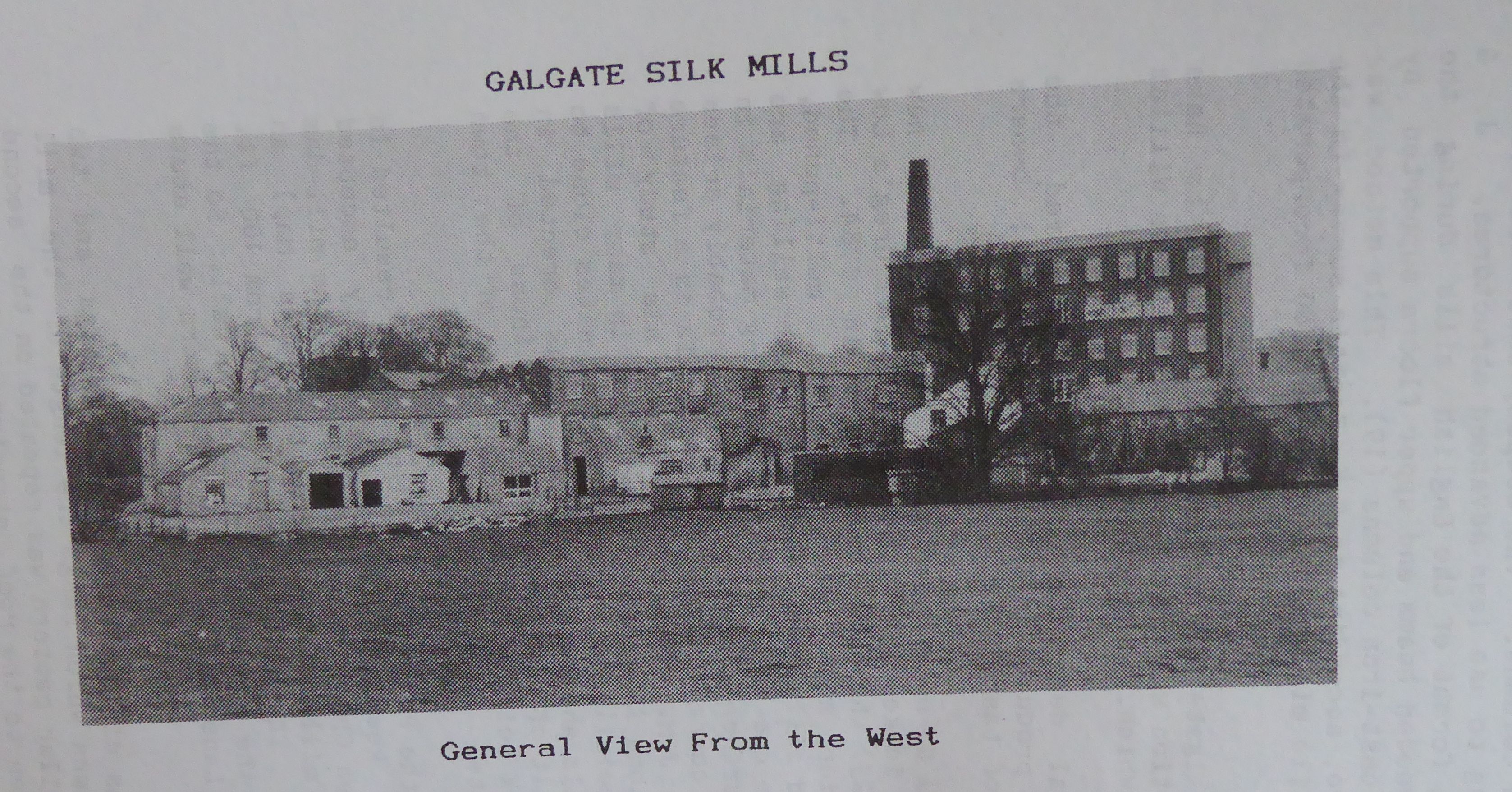

The mill buildings, acquired in 1792, can be regarded as traditional or vernacular structures as defined by a number of writers on the subject, especially Owen Ashmore (10) and Jennifer Tann (11). Whilst the original function of the building was not that of a textile mill its structure and design closely follow the traditional pattern. As a water-mill it could have had a multi-functional role similar to many of the South Westmorland mills of the period (12) or, like the mill at Bonds near Garstang on the River Wyre, operated purely as a corn-mill.

The external appearance of the building is one of solidity, a characteristic of most of the early industrial buildings. The random-laid gritstone walls, originally whitewashed, the small window spaces and the slated roof all bear considerable resemblance to the Bonds Mill at Garstang (13). These similarities could also be recognised in some of the early purpose built textile-mills such as the earlier parts of Kirkham Linen Mill (14).

The main building measures 112 ft. long and 26 ft. wide. These dimensions produce a long narrow building, a feature which both Ashmore (15) and Tann (16) see as being typical of the early textile mills. This narrowness of the mill resulted from the necessity to use single beams to span the interior without additional support apart from that provided by the thick load-bearing external walls. Window spaces were kept to a minimum size in order not to further weaken the structure although each of the three floors do carry a range of eleven small windows. Each of the windows is glazed with either nine or seven small panes in a manner similar to that used at Cromford Old Mill in Derbyshire (17).

Internally the comparative narrowness of the building allowed for an uninterrupted floor space whilst the heavy wooden beams supported the floor above. It was only later, in the 19th Century, with the introduction of heavier machinery that cast-iron columns were inserted on the ground floor as additional support for the beams. On the top floor, where roof-lights provided additional lighting, the timber roof trusses are exposed and provide a further example of the use of traditional methods in the building of these early industrial structures.

Phase Two. (See Map)

At the same time as the Galgate corn-mill was being converted for a new role, advances in mill design and construction were already in progress elsewhere. The vernacular traditions were being replaced, to a considerable degree, by a more functional approach to industrial building. William Strutt's Derby Mill, with its cast-iron columns, paved brick arches and cast-iron beams, was beginning to take shape in 1792 (18). This 'fireproofing' of a mill by the elimination of the timber structure was to become a feature of later mill building with examples such as Benyon, Benyon and Bage's Shrewsbury Flax Mill of 1796 being quickly erected.

When plans to extend the Galgate enterprise were laid in the early 1830s the constructional details mentioned above do not appear to have been followed except in the case of the cast-iron columns. The company does not however appear to have been alone in continuing to use less advanced structures. J. & saw the typical internal format of the English mills during the period 1825 - 1865 as being one of wooden beams and upper floors supported by both the external walls and lines of cast-iron columns (19). This method was also in use at a more local level where, according to N.K. Scott's survey in the 1960s, the majority of Preston's textile mills built prior to 1880 incorporated the features outlined above (20).

Externally the Second Phase of the Galgate mill buildings also appear to have lagged behind as far as their construction was concerned. By the 1830s William Fairbairn was already designing mills which, as he points out, had:

'no pretention to architectural design but generally improved the appearance of the buildings and produced in the minds of the mill owners and the public a higher standard of taste.' (21)

Yet the Fairbairn design features (22) do not appear on the facade of the new Galgate mill. Its appearance is more in keeping with that of Samuel Greg's Low Mill at Cat on in the Lune Valley (23) which had been built in 1784. The characteristic features of the earlier mill, rows of large, multi-paned, rectangular windows, stone lintels and sills, and local gritstone walling are featured in Phase Two at Galgate. The use of traditional building materials in preference to the red brick of areas further south in Lancashire probably arises because of the availability of locally quarried stone. Again this is a feature that is parallelled in other areas. J.M. Richards notes, in his study of textile factories, the use of local stone in preference to brick in many mills built after the 1790s. This was especially so on water-powered sites close to river valleys (24). The various mills and other large buildings erected in Lancaster during this period were built of similar materials to those of the Galgate mill. The stone for this work being quarried on the edge of the towe and in the Quernmore valley above Galgate.

The peculiarities of the site on which the Phase Two building stands resulted in the shape of the mill being out of keeping with the generally accepted rectangular trend. In the space between Chapel Lane to the east, the mill-dan to the north-east and the original mill to the north-west (see Map) an irregularly shaped structure was built. The mill tapers in width from 100 ft. at its south-western wall to 60 ft. at the opposite north-eastern wall. So the eastern wall follows the line of Chapel Lane whilst the south-western wall abuts the wall of the original mill.

The ground floor of the new building was divided into five large bays and tw smaller ones by rows of cast-iron columns which range the length of the mill supporting wooden cross beams. A similar pattern was repeated on the second floor whilst the top floor remained open to the roof structure. The ground floor was used for the preparation and dressing of the fibres prior to spinning whilst the first floor housed the self-acting mules. The use of cotton spinning methods or 'short-spinning' in the spinning of silk waste was a method that was rarely used in the silk trade and the Galgate company pioneered its development.

This accounts for the presence of the mules rather than the flyer spinners that were normally used in the spinning of silk by the long-spinning method (25).

Power for the machines came via overhead shafting coupled to belt drives. The supporting blocks for the shafts running down the centre of each bay and, Today, independent of the cast-iron columns, were fixed to each cross beam. with this part of the mill cleared of machinery, these rooms. appear quite spacious although not to the same extent as those of the later mill where cast- iron columns and wooden beams were more widely spaced out and the ceilings considerably higher.

Phase Three (See Map)

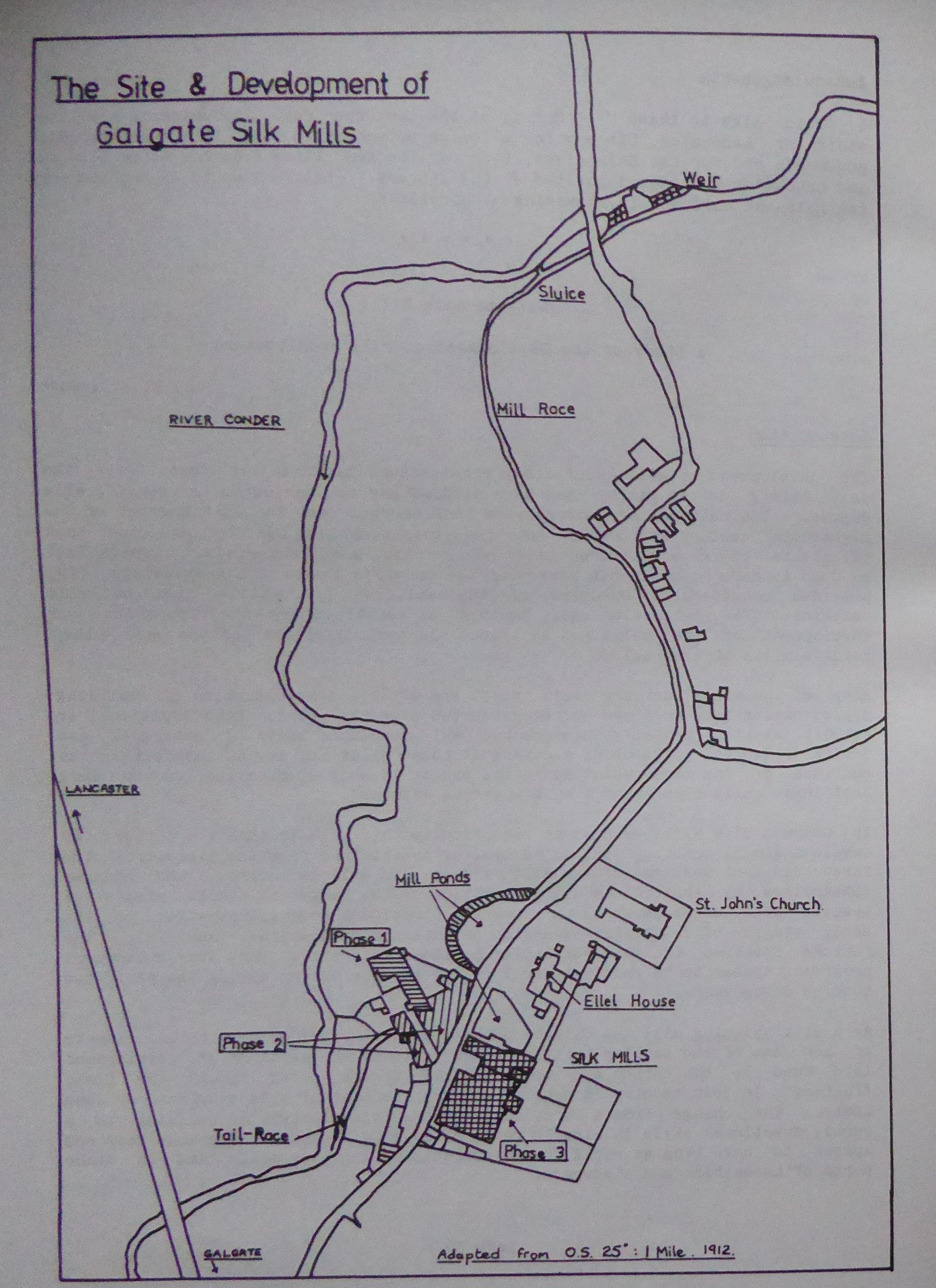

The third and final phase of building at Galgate can be easily defined even by the inexperienced observer. In fact, if one was not aware of the links between this building and the earlier structures on the opposite side of Chapel Lane, it might possibly be thought to have little connection with them. Whilst the earlier buildings, with the gritstone facades, appear to blend into their surroundings, the square, five storey, red-brick mill of 1851 stands out above them and the rest of Galgate. It would not appear to have been out of place in the middle of a Lancashire mill town but in this semi-rural setting it appears to be at odds with its surroundings.

John Armstrong Jnr., the son of one of the original partners in the company, is credited with the design and construction of the Phase three buildings (26). He appears to have taken note of the techniques and designs that were current in the mid-19th century whilst, at the same time, retaining many of the features that were already present in the 1830s mill.

Fairbairn's mill designs of the late 1820s appear to have gained favour as the external appearance of the building shows. Internally there appears to have been no thought given to building a completely iron-framed and fireproof structure even though mills of this type had been in operation for well over half a century. Ashmore notes that the use of cast-iron columns and beams helped to produce a characteristic style of textile mill during the period 1830- 1870 (27). The various reports of the failure of certain cast-iron structures during the 1830s and 1840s, for example that of Lowerhouse Mill in Oldham in 1844 (28), may also have had some effect on Mr. Armstrong's thinking when planning the new building.

Externally the mill bears many of the features associated with the early Victorian textile mills. The three aisled building has, on its western and eastern facades, a range of ten and nine windows respectively on each of the five floors. The lesser number on the western side being due to the presence of the stairway at the north-west corner of the mill. The deep window-frames, measuring 12 ft. by 6ft. and each containing fifty-six panes of glass, are set between sandstone lintels and sills. As with the windows in the earlier phases of building the lintels are set flush with the wall whilst the sills project slightly from it. On all the windows the top two rows of panes form inward opening frames which could provide a considerable draught onto each floor, feature which probably would not have been appreciated in a cotton spinning mill where the humidity was of greater importance than in a silk mill.

The increased depth of windows, when compared with the five and seven feet of the windows in the other two buildings, provides some evidence of the need for a lighter form of wall construction. This factor was probably due to the transfer of a certain amount of structural load from the external walls to the internal framework. The reduction in the width of the intervening brick piers when compared with that of the stone piers of the earlier buildings also provides further evidence of a reduction in the load-bearing requirements of the external walls.

Whilst the the pattern of the windows retain Georgian proportions the only other decorations on the mill facade, that of the simple brick pilaster at the four corners of the building and the low cornice, are features that become more regular and prominent on the post 1830s mills. Their introduction into mill design is attributed to William Fairbairn, the fact of which he appeared to take some degree of personal pride (29). The roof of the building still reflects earlier ideas rather than the flat, often water-covered roofs of the later mills. The cast-iron water tank, atop the north-west corner of the building, is a feature of many mid-19th century mills in which sprinkler systems were installed in case of fire. Later mills were to disguise this safety feature within Hotel de Ville' type towers or Rococo and Baroque domes (30).

The internal structure of the mill shows only slight variation from the mill. The 10,000 square feet of floor space on each floor is divided into eight bays by seven rows of cast-iron columns running east to west. Five columns support each longitudinal wooden beam to which is fixed the wooden joists supporting the floor above. The main difference between these columns and those of the earlier buildings is that they are topped by cast-iron saddles through which the beams are threaded. The saddle then connects through the ceiling to the base of a further column on the next floor. Each beam is bolted to a 'fish- plate' at the base of the saddle. N.K. Scott noted the use of this technique in the Preston mills during this period chiefly as an attempt to stop beams from falling due to the pressure of the column head on the beam (31). Secondly, it also allowed shorter beams to be used as they could be butt-jointed within saddle and then bolted in place.

The large window spaces provided considerably more light than those in the earlier mills. Each bay is illuminated from both east and west with additional windows in each end bay plus further light from a range of four windows in the northern and southern walls. Thus, together with the increased ceiling height of 15 ft., this extra light provided the operatives with greatly improved working conditions, when they were compared with those in the older sections of the mills.

The final feature of the Third Phase of building is the 140 ft. high mill- chimney. This stands slightly to the north-east of the main mill block and adjacent to the original boiler and engine houses built in the 1830's. Built of brick, the chimney is square in section rather than round and tapers from about the 40 ft. level upwards. This type of design is normally associated with mill construction yet the position of the chimney away from the mill is a feature of later mill construction (32). Thus, as with many other features of the Galgate mills, the chimney provides something of an exception to the rule.

View from the North West of Phases One & Two of the Mills

Conclusion

This study has traced the development of a particular group of mill buildings a period of some 60 years during the late 18th and first half of the 19th centuries: a period during which the British textile industry underwent a considerable transformation. These changes are reflected in the development of mill buildings in the country's major textile manufacturing areas. New methods of production often called for the alteration of or the replacement of existing buildings. The advances in metal technology helped to remove many of the limitations on the size and the shape of the buildings.

The Galgate mills do tend to show that these innovations took time to filter through to the outlying pockets of the textile industry and into textile trades. Even though national trends were followed to some degree they introduced much more slowly and were used alongside the traditional vernacular methods that were present in the area prior to the opening of the first part of the mill complex.

References

1. 0. Ashmore, The Industrial Archaeology of Lancashire, (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1969) p.47.

2. Ibid. pp. 47-49.

3. J. Tann, 'Building for Industry', in The Archaeology of the Industrial Revolution, ed. B. Bracegirdle. (London: Heinemann, 1973) p. 167.

4. 'Report of the Factory Inspector on Cotton, Woollen, Worsted, Flax and Silk Factories in Each Parish in the County of Lancashire. May 1st 1835' quoted as Appendix IX in E. Baines, History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster, Vol. IV. (London: Fisher, Son & Co., 1836) p. 780.

5. Oldest Mechanical Silk Spinning Mill in the World but "Always Ready". in The Silk Journal and Rayon World. (London: April 1937) Unpaginated.

6. J. Tann, op. cit. p. 168.

7. M.H. Helm, The Development of the Industrial Communities of Galgate and Dolphinholme mainly in the 19th Century. M.A. Thesis (University of Lancaster, September 1969) p. 18.

8. Article in The Silk Journal and Rayon World, op. cit. Unpaginated.

9. E. Baines, op. cit. p. 780.

10. 0. Ashmore, op. cit. p. 47.

11. J. Tann, op. cit. p. 182.

12. J. Tann, ibid. p. 160.

13. J.M. Richards, The Functional Tradition in Early Industrial Buildings (London: The Architectural Press, 1958) p. 123 Illustration.

14. 0. Ashmore, op. cit. p. 278 Illustration and p. 278.

15. 0. Ashmore, ibid. p. 47.

16. J. Tann, op. cit. p. 169.

17. J. Winter, Industrial Architecture, A Survey of Factory Building (London: Studio Vista, 1970) p. 26 Illustration.

18. T. Bannister, 'The First Iron-Framed Buildings', in The Architecural Review (April 1950) p. 236.

19. 0. Ashmore, op. cit. p. 48.

20. N.K. Scott, The Architectural Development of Cotton Mills in Preston and District Vol.1, M.A. Thesis (University of Liverpool, 1952) p. 66.

21. W. Fairbairn, A Treatise on Mills and Millwork: Part II, On Machinery of Transmission and the Construction and Arrangement of Mills, (London: Longman & Co., 1863) p. 114

22. cf. details of Phase Three Building in this article.

23. J. Winter, op cit. p. 32. Illustration incorrectly labelled 'White Cross Mill' cf. 0. Ashmore op. cit. p. 254.

24. J.M. Richards, op. cit. p. 77.

25. Article in The Silk Journal and Rayon World, op. cit. Unpaginated.

26. The Silk Journal and Rayon World, ibid.

27. W. Fairbairn, op. cit. p. 114.

28. 0. Ashmore, op. cit. p. 51.

29. W. Fairbairn, op. cit. p. 116.

30. N.K. Scott, op. cit. p. 66.

31. 0. Ashmore, op. cit. p. 57.