The Preesall Salt Industry, Part 2, 1892-1911

by Rosemary Hogarth

By the end of 1891 the United Alkali Co had decided to exploit the Preesall rocksalt deposits in three different ways; Ammonia Soda Works, Salt Works and Rock Salt Mining (1).

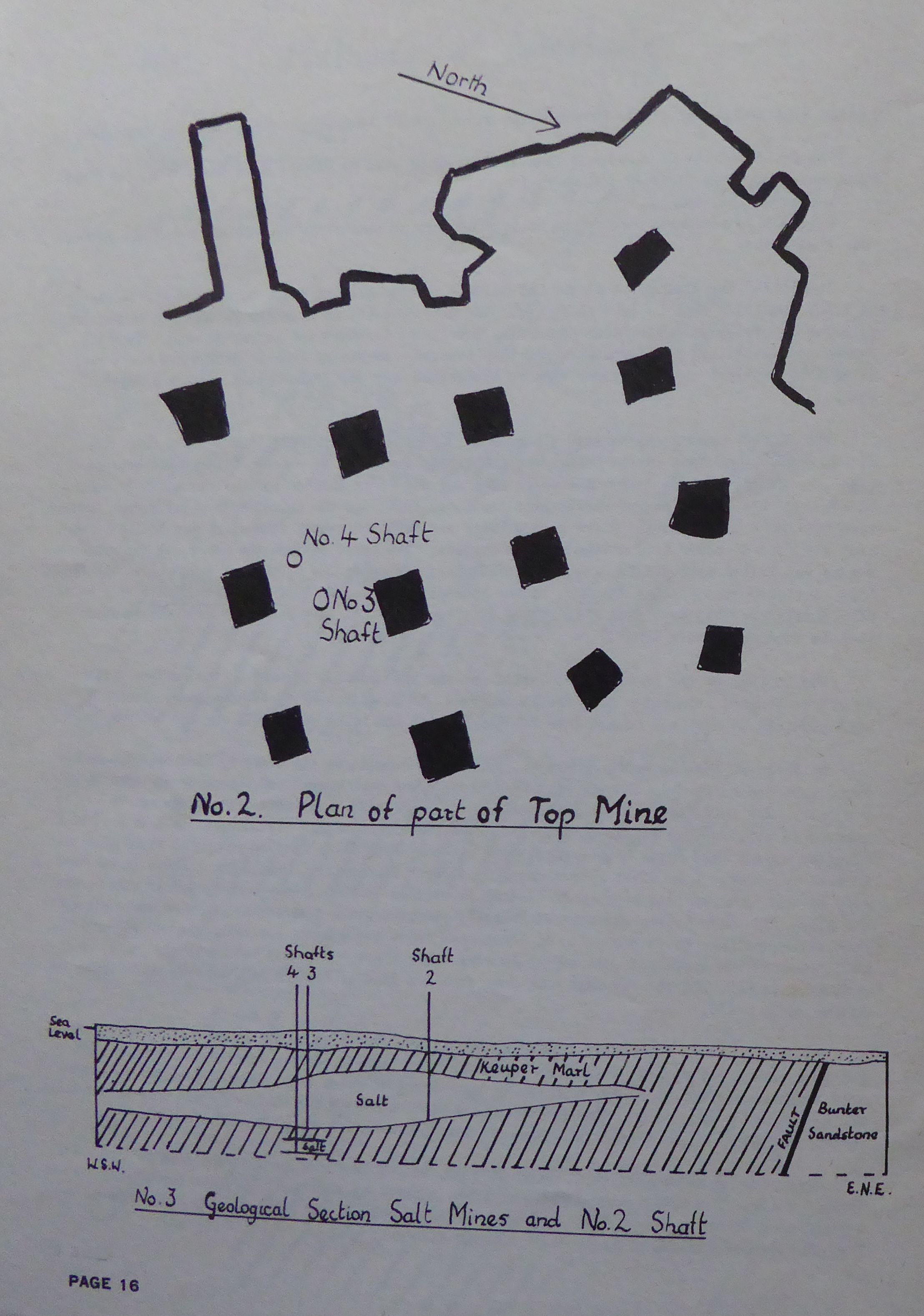

In 1892 the Company built a "modern" Ammonia Soda Works on a 42-acre farm, purchased the previous year from Mr T Riley of Fleetwood, adjoining the railway sidings at Burn Naze. Four more boreholes, Nos 28, 29, 30 and 36, were put down in Preesall for brine to supply the Salt Works and the Ammonia Soda Works. By 1897, 109,000 tons of salt had been taken by solution from these four boreholes (2).

A pumping station with boilers and force pumps was built in North Field near Nos 28, 29 and 30 boreholes. The brine was now being "forced" to the surface by putting extra pressure on the water. Another American well-borer, Mr Charlie Olston from California, put concentric steel tubes down the boreholes. An eight inch diameter tube was put to the bottom of the salt deposit and water pumped at 160-180 lb pressure down the three inch diameter central tube. Brine returned at about 30 lb pressure (3). The forcing system was very efficient; borehole No 30 yielded at times 1,600 tons of salt in brine per week (2).

Water for the brine forcing and for use in the Ammonia Soda Works was obtained from No 17 borehole (1) and new wells, the Parrox Wells, were sunk east of the faultline. The Parrox Wells, Nos 34 and 35, commenced operation in 1894 supplying 45,000 gallons of water per hour (2). In 1896, on the advice of the geologist Mr Charles E de Rance, wells were sunk about a mile and a quarter east south east of the Parrox Wells on an acre of land which became known as "Klondyke".

The United Alkali Co commenced rocksalt mining in 1893 by putting down two shafts, Nos 3 and 4, to an approximate depth of 450 feet.

Rocksalt is extremely soluble so it is necessary to absolutely exclude all water and moisture from a saltmine.

In sinking the shafts the miners had to pass through glacial drift to a depth of 114 feet in No 3 and about 124 feet in No 4 shaft (4). The glacial drift in Preesall is composed of reddish coloured impermeable boulder clay containing some large boulders and layers of sand. The sand layers hold water and form springs where they outcrop - eg Spring Bank SD 346798 and Fairy Well SD 367476. Springs may also occur when an excavation into the boulder clay reaches a layer of sand.

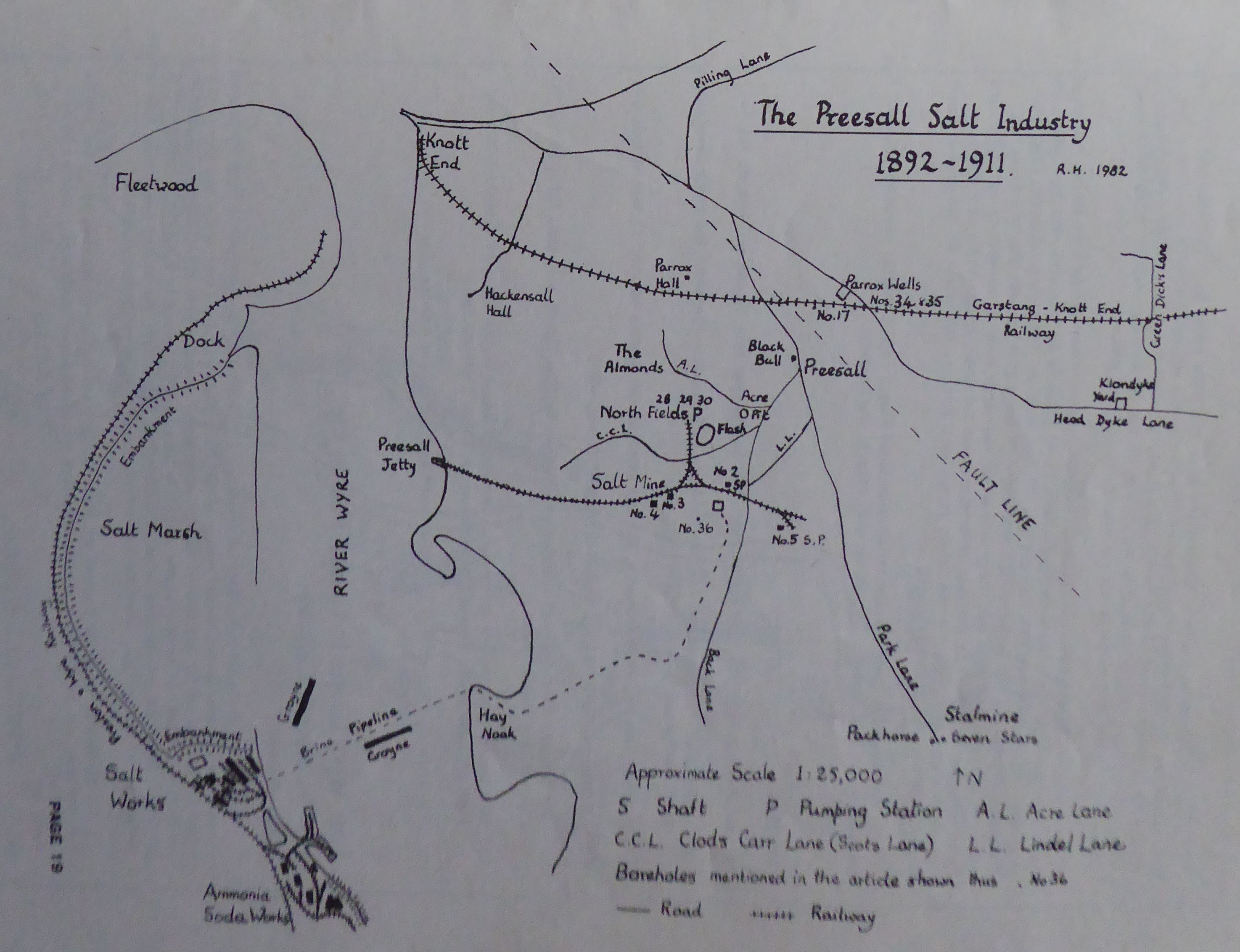

The 7 1/2 foot square shafts were timbered down through the boulder clay. In the clay, the miners encountered sand layers containing considerable amounts of water and large ice-marked limestone boulders which filled the shaft area and had to be blasted before they could be raised to the surface. The timbered shafts were continued down into the Keuper Marl until a safe foundation was found in the marl. There a blue brick and Portland cement foundation was built and cast iron six foot diameter tubing taken to the surface. The space between the tubes and the timbered shafts was filled with puddle clay, thus absolutely excluding the seepage of water (2). The shafts then continued down through the marl to the rocksalt and stopped in a good bed of salt at a depth of approximately 450 feet from the surface. (Later, in 1904, No 4 shaft was deepened to about 900 feet to form the "Lower Mine".)

The bottoms of the shafts were blasted out and the rocksalt brought to the surface until a cavern was formed into which both shafts dropped. Mr Singleton, from Village Farm, Preesall, employed lads to cart the rocksalt to Pilling Station and bring back slack for the boilers (3).

An Improved Stanley Heading Machine, powered by compressed air drove 4 foot headings to the east, west and north from the cavern. Once those areas were opened out, blasting was used to get the salt. The Rock Getters, who worked a 9 am to 3 pm shift, used hand-drills, powered by compressed air, to bore slantways into the rocksalt. It took only five minutes to bare a 13 inch diameter hole 5 feet deep. Black gunpowder "bobbins" were then "stemmed in" until flush with the edge of the rock. Long wheat straws charged as fuses were pushed through the bobbins in the hole left by the "pricker" and a piece of candlewick twisted to them. They were sealed in with rocksalt and grit. The Rock Getter would shout "Fire!", everyone would take cover; then he would light the candlewick and take cover himself. At least once there was a large explosion when an air-pocket was struck during blasting; men and tools were flung about but no-one was seriously hurt. O another occasion, 200 tons of salt came down from the roof of "Long Drag", luckily where there was no-one working (3).

The Rock Getters left their drills at the Blacksmiths' shop on the surface every afternoon and took freshly-sharpened drills each morning. They carried candles (for obvious reasons the rock face was not lit by electricity) which they stuck in moist clay obtained from the clay-tub at the bottom of the shaft. Maddock picks were used to smooth the roof. The men ware blue flannel vests, long johns, long stockings, clogs and spats to keep out the salt particles (3).

After the Rock Getters' shift ended at 3 pm, the cutting machine men went down to work until early morning. The rotary undercutting machine, powered by compressed air, was operated by a man sitting on a "crab" anchored into the rock. Messrs Dickinson and Raby were two Rock Cutters. They surfaced at the end of their shift covered with dust (3).

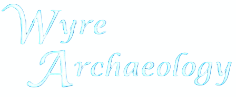

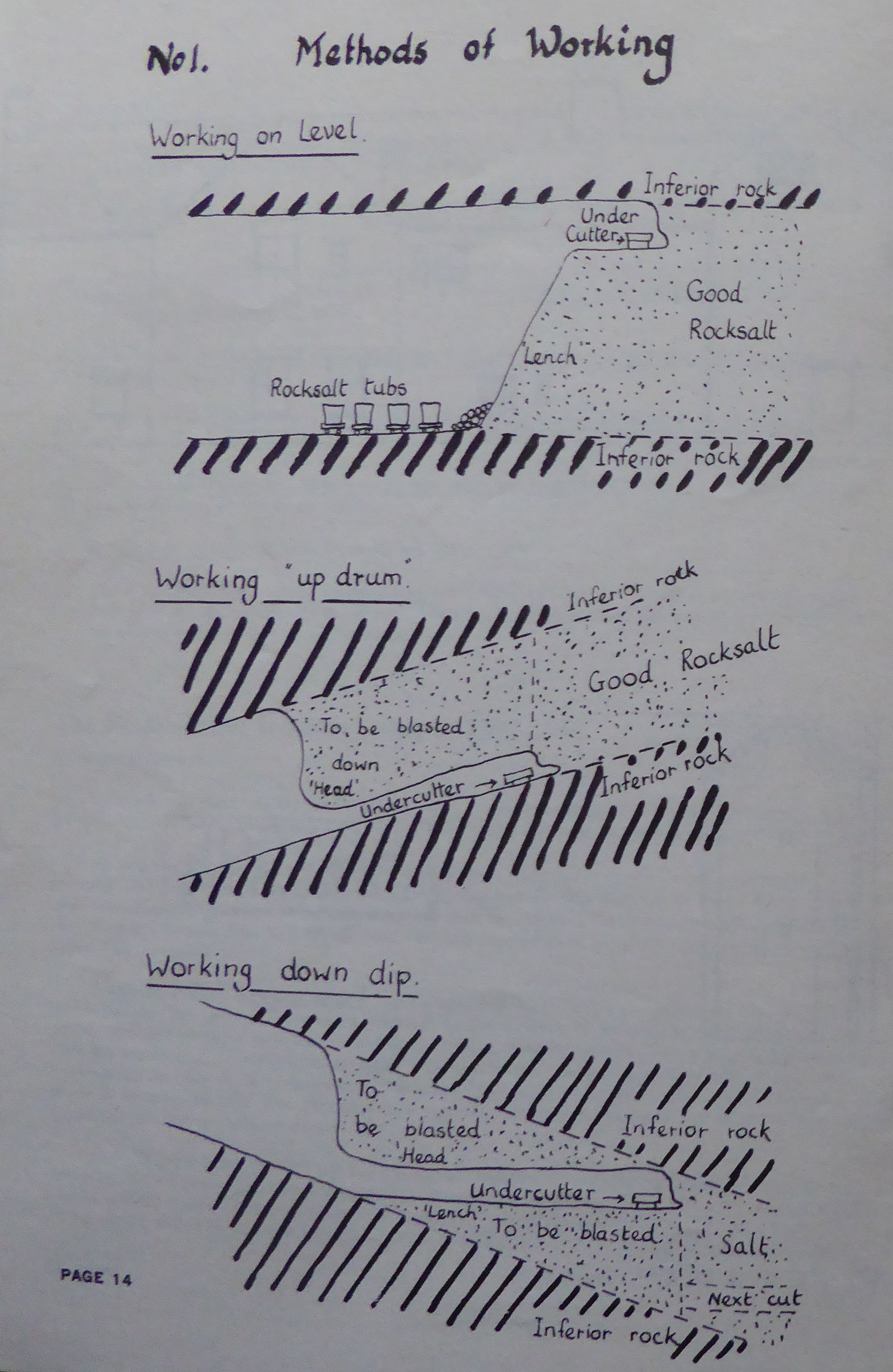

The upper bed of rock salt which was first opened out is about 40 feet thick and dips to the northwest at a rate of 1 in 34 (2). The method used by the Rock Cutters and Getters to open this up is shown in diagram 1. Eventually the caverns were between 16 and 40 feet high with pillars of salt 60 feet square left every 105 feet as support (see diagram 2). In the lower mine the salt was mined in caverns 22 feet high.

After blasting and cutting, the rocksalt slid down the face to the floor of the mine where it was sorted by the Rock Pickers, who, using candles set in clay for light, picked out the lack pieces" or tailings which were sent to the grinder. This "fine-screened rock" was set to different markets according to quality, and was collected by local farmers for sweeting de pastures, arable land and use on icy roads. "Bristol Orders" were the finer tailings which were used in winter on the roads of Bristol to prevent horses from slipping (3). Tine-screened rock" was also exported to Belgium, Holland and Denmark (5). In 1909 Johnny Staz, believed to be over 80 years of age, worked picking out "black pieces" by candlelight down Marbury", a section of the top mine (3).

The 1 in 3 1/2 slope facilitated the working of the railway which brought the 30 cwt tabs of rocksalt from the face to the shaft. The Rock Ferriers, working day and night shifts, filled these tubs. Winches, powered by compressed air, pulled a "train" of four bogies each containing a rocksalt tub or hoppet, up to the shaft from the westerly workings such as "Long Dip" and "Marbury Dip". No power was needed for the bogies from the easterly workings such as p and "Long Drag"; the full tubs came down by their own weight to the shaft, pulling up the empties (3)

At the shaft, three chains were hooked to the rocksalt tub which was hauled to the surface. There were two methods of signalling to the surface, an electric bell and a handline for emergencies which worked a hammer and gong on the surface. The rocksalt tubs were also mad as lifts for the men. Two men descended inside the tub with others standing on the rim holding the chains (3).

The same winding gear was used for both mines, a larger drum and longer rope being need for the lower mine, the descent into which was much quicker. The two shafts were twenty feet apart. There were two ways out of the upper mine but only one from the lower mine. No gases were encountered in the rocksalt so the natural air plus the exhaust from the compressed air machines provided enough ventilation. The mines were lit by electricity, mercury vapour lamps, except for the areas where blasting was taking place (3).

The compressed air was sent down the shaft to a receiving cylinder or Lancashire boiler. In 1909, Mr Harold Daniels worked as a 14-year old at shaft No 3 gantry in the upper mine, fitting compressed air pipes to blasters and fastening the rocksalt tubs to be lifted up the shaft from the bogies. Mr Daniels earned six shillings a week which rose to six shillings and sixpence when he was 16. (There was no pay for holidays.) He thought it was very beautiful down the mine with the red, yellow and white salt and the black marl and gypsum. There seems to have been a great camaraderie among the men. The lads at the shaft used to play pranks on the miners. At Iunchtime the cans of tea were lowered down the shaft. One practical joker managed to fuse the mine's lighting system by "wiring up" the miners' tea cans. The ordinary salt miner earned a guinea week in 1909. Mr Daniels' father, who came from Northwich, Cheshire, worked in a gang of sixteen Rock Ferriers on piece work at a rate of five pence per ton. The gang was paid a lump sum at the end of the week. The share-out caused some arguments.

Many families such as Whitlow, Maddock, Rowe, Davies, Fairhurst, Phillips and Danials, came from Northwich, Cheshire, to work the salt and teach the Preesall folk saltmining. Mr Anderson, the Mine Manager who lived at Fernbreck House, himself from Northwich, had Lindel lane well drained on both sides to provide a good path for men to walk or cycle to work. Company houses were built Down Town and on Acre Lane. Workers living in Knott End walked along the railway line then out through the Almonds where the railway branch line would eventually be laid.

Dr Taylor and Mr John Edward Carter, Mine Secretary, ran a medical club; sixpence per week covered the miner and his family's medical expenses (3). The Tontine Club, which met at the Black Bull Inn, ran from 1900 to 1926. Members paid sixpence per week up to 15th June 1910. After that because of the National Insurance Act, each man had fourpence deducted from his wages so the Club dropped its subscription to threepence a week but the benefits remained the same. On 15th February 1902, James Whittaker was awarded nine shillings a week after falling on a slippery road. When a member was awarded benefit, the club officials kept a close watch on him. He was not allowed to go out at night. On 10th December 1900, Jack Parsons was fined half a crown for being out after 8 pm (7). It is believed that similar clubs, such as the Mechanics, were run from the Packhorse and Seven Stars Inns in Stalmine (3).

Surprisingly there were few very serious accidents. The worst took place at 11.45 am on 12th June 1905 when Fred Davies, aged 37, and Arthur Phillips were working on a staging in No 4 shaft dressing the sides of the shaft. Three shots were fired in the upper mine, bringing down the shaft some large pieces of rocksalt which hit the staging on Fred Davies' side. Arthur Phillips tried unsuccessfully to grab Fred Davies who fell 420 feet to his death. He was buried in Northwich, his home town.

The population of Preesall-with-Hackensall, which had been over 800 since 1841, rose from 893 in 1891 to 1,421 in 1901 and 1,718 in 1911. The number of inhabited houses increased from 185 in 1891 to 312 in 1903 (6). As the local people became more skilled, a two-way movement of families grew up between Preesall and Cheshire.

Preesall became famous. According to "The Times" November 1906:-

"A descent into the Preesall pit is an experience of unusual interest. Though the mining operations have only been conducted for a dozen years, the weird, lofty, cavernous vaults formed by the excavation of over a million tons of salt are sufficiently impressive, when illuminated as they are by electricity, to bewilder the spectator who visits them for the first time. The rocksalt is so dense and tough that it is necessary to win it by blasting. It is discharged directly from the mouth of the mine into railway trucks beneath and is then run down to Preesall jetty, where vessels and steamers up to 1,600 tons, exempt from all dock dues, can be loaded with great rapidity. With such enormous supplies of salt at their command, the United Alkali Company can not only supply all its own wants but has also become the second largest white salt manufacturer in Great Britain, having put down extensive evaporating works both at Fleetwood and Middlesbrough. Fleetwood Rock Salt has established itself a very high reputation both in the Australian and South American markets, especially for cattle purposes. For those two particular markets, the Rock is not only loaded direct from Fleetwood docks but is also shipped from Liverpool and elsewhere" (5).

Vessels loading salt at the Company's Burn Naze jetty were also exempt from dock dues. The domestic salt produced at the Salt Works by evaporation was renowned for its brilliant colour and flocculent nature and typed according to grain. In 1906 "Common" salt was largely exported to the Baltic, Canadian and Continental markets. In India and Burma "Fleetwood Butter Salt" was highly appreciated for its brightness, whiteness and lightness. For fish curing the salt was shipped to the Faroes and Iceland (5).

By 1911 the mine was producing 115,000 tons of rocksalt per annum (25,000 tons less than the peak production year of 1906) and water from the Parrox and Klondyke Wells was being pumped to a reservoir at the new Pumping Station built in 1905 next to No 5 shaft (2). From there the water was pumped under the River Wyre to the Ammonia Soda Works.

A gradual subsidence had been taking place since the 1890s round No 21 borehole and filling with rainwater. By 1911 this "Flash" covered five acres and the water from it was used by the Company as condensing water in its vacuum salt plant, and also for forcing brine. The vacuum salt plant used the exhaust steam from the engines at the pit head for boiling brine which came out as a thick damp salt solution and was evaporated in three pans.

The "Flash" did not worry the Company. However, shortly after midnight on Sunday 3rd November 1901, a serious subsidence had occurred in North Field round No 28 borehole. The land continued subsiding. By 5th November 1901 the hole was 100 feet deep and 135 feet in diameter (2). The "Fleetwood Express" of 6th November 1901 reported - "A large plot of land near the mines has collapsed entirely, leaving a very large hollow and the earth round is cracked in all directions. As a precautionary measure, a quantity of machinery was taken out of the works on Monday but considerable anxiety is felt for the safety of the tall chimney, the cracks in the ground almost extending to the site of the chimney".

By 1911 the North Field subsidence had stabilised itself into a roughly circular hole 300 feet in diameter but like Acre Pit (1), it was a warning to the Company.

References

1. The Preesall Salt Industry, Part 1, 1872-1891 in The Over Wyre Historical Journal Vol 1.

2. FJ Thompson, "An Account of the Salt Deposits at Preesall - Fleetwood and their Development" unpublished property of ICI 1927.

3. Mr Harold Daniels, my great-uncle, who has supplied the details of work in the saltmines.

4. RL Sherlock "Rock Salt and Brine" Geological Survey 1921.

5. "The Struggle for Supremacy" a series of articles in "The Times" 2nd, 9th, 12th, 14th, 19th, 21st and 26th November 1906.

6. Dr J Spencer Low's report to the Local Government Board on the Sanitary Circumstances and Administration of the Preesall-with-Hackensall Urban District 1904.

7. RG Shepherd, "Ancient Ways of Saving Cash" West Lancashire Evening Gazette.