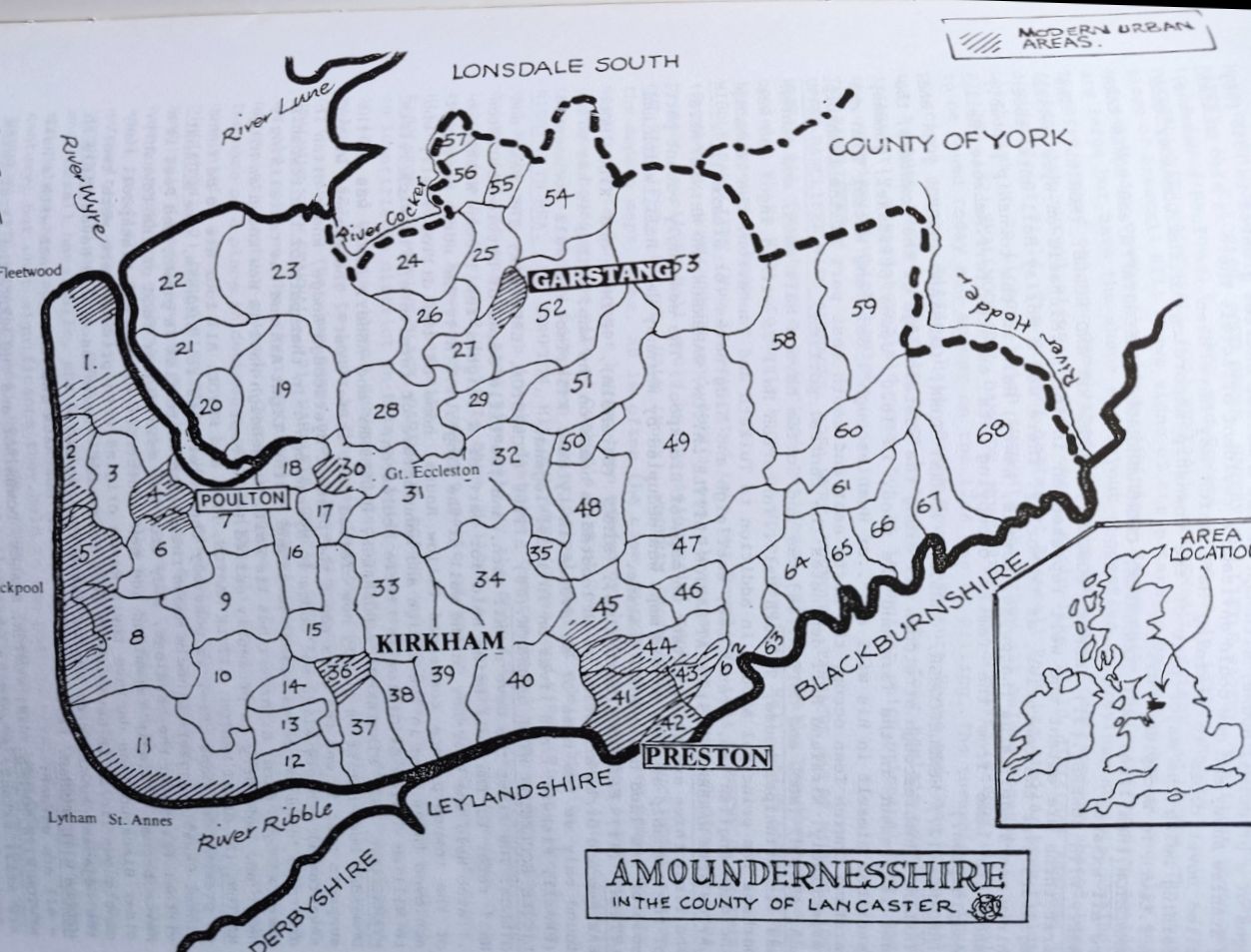

Quarterlands in Amoundernesshire, Co. Lancaster

By Richard Watson

The question of how land division was managed in the pre-medieval period over the British Isles, and also the tangible evidence for its existence, continues to evade precise answers.

One difficulty is that there appears to have been a multiplicity of regionally determined conventions about land holdings and their consequences on taxation and on social organisation, but the boundaries within which particular conventions operated require some care to determine. As an analogy, in the consideration of early modern vernacular architecture of north Lancashire, the relics of earlier forms seem to have governed both what survived in the organisation of the local microcommunities and to have had an important influence on the choices made by their inhabitants during the early modern period from 1650 to 1720. The picture is further complicated, first by the uncertainty about whether the Harrying of the North by William I and his followers on the North East, equally affected the North West, and secondly by doubt about whether the locality had more in common with the Isle of Man and North Wales and their This paper seeks customs than with Cumbria and the conventions followed there. to consider some of these general issues, and by means of a gazetteer based upon both documentary and fieldwork evidence, to suggest that the area followed both the Manx and North Walesian pattern in having quarterlands as primary local division of land.

QUARTERLANDS.

What are, or more correctly, what were quarterlands? In the area under consideration the present writer contends that they are the vestiges of an ancient fiscal division of a township with pre-Conquest roots. In the Isle of Man, which is the closest predominantly Celtic community to Amoundernesshire, a Quarterland (1) is a division of land, originally the fourth part of a Treen or Balla (2). The Welsh name for township is Tref, and it forms part of a system created in multiples of four; from four acres upwards. The whole system is given in idealised form in the Book of Iorwerth (Llyfr Iorwerth), which also tells us that certain food rents and cattle renders were due to the king or his successor (3). How much of this relates to the Hundred of Amounderness or, indeed, Lancashire as a whole?

"It is of interest to find that the Thegns of the land 'Inter Ripam et Mersham' at Domesday also paid one quarter pence an acre, or 2 ores (32 pence old style) for 128 acres, which was assessed at eight oxgangs, sixteen acres per oxgang. Further, many of the early estates of Amounderness that were fractioned into sixteenths contained exactly two caracutes or 256 acres,...."(4) It is also interesting to note when referring to Domesday Book entries concerning the Welsh Marches "....in the nearby manor of Bellingham there were four freemen with four ploughs who rendered four sesters of honey, a characteristic Welsh render, and 16d as 'custom'. This assessment in fourths suggests that the schematic arrangement in the Book of Iorwerth may have ante-dated 1066 and, possibly the English conquest of Cornwall in the tenth century, for there too, a system of fours is found in customary measures of area. "(5) Much of the above quotation could refer to the Fylde of Amoundernesshire.

As late as the thirteenth century, Cockersand Abbey received a grant of a Sixteenth of Helrecar meadow belonging to an oxgang of land and a sixteenth of the waste of the vill of Carleton (6). At the same period in Ashton on Ribble a grant was made of sixteen acres and a sixteenth part of the fishery of Ribble. (7) The large township of Woodplumpton in 1838 (8) was still divided into Plumpton Quarter, Catforth Quarter, Bartle Quarter and Eaves Quarter, proclaiming on the modern Ordnance Survey maps that shew field divisions, that each Quarter had an area which would have been the townfield and strip ploughed. Hewitson, in his 'Northwards', relates the legend of the four lords of Barnacre; perhaps folk memory of the four principal land holding freemen who were dispossessed by a later pragmatic lord of the manor who wished to bring Barnacre to a more economic viability. (9).

THE HARRYING OF THE NORTH

For a reasonably undisturbed indigenous population, with deep rooted customs to have existed at the time of Domesday should not presuppose they would survive the harrying of the north by William I. The question is, was the North West subject to the punitive expedition in 1069-70? To quote the region's early historian, Edward Baines, (10) "...and according to William of Malmesbury, confirmed by Roger Hoveden and Simeon of Durham, the whole country was laid waste from Humber to the Tees." The reference is entirely to the east of the Pennines; the present writer is of the opinion that had there been any significant operation to the west, the names of Mersey, Ribble or Lune would have found a place in the report. no wasting of the lands of Kapelle (11) is of the opinion that there was Amoundernesshire after 1066 because they were waste before that date.

It must be borne in mind that the area we now know as Lancashire (pre 1974) was not settled by the Norman administrative classes until two or three generations after the Conquest, and then by Low Normans from the oatlands of western Normandy and eastern Brittany, the descendants of the Norsemen who were thought to have sailed from this west coast of ours to colonise West Normandy (12).

It was also difficult terrain. The sophisticated engineering and construction skills of the Roman administration had long since become overlaid, and their roads would be fragmentary or otherwise obscured. Referring to the period c.616, Nora K. Chadwick writes 'The land routes north through Lancashire, though not impossible, as we know from references in Welsh bardic poetry, was at all times a difficult one, unsuitable for movements of large bodies of men. The south was forest clad; the centre boggy and waterlogged, the rivers run from east to west, and were not easily forded in their lower courses. To the east the Pennines stretched from north to south, inconveniently steep to the west." (13) One thousand years later, in December 1616, the steward to the Shuttleworths of Gawthorpe could write in his accounts "...given to a woman which did direct my mistress companie over Inskippe moss..." (14).

From the above, the present writer postulates the opinion that Amoundernesshire was not included in the harrying of the north. Apart from the very obvious difficulties of sending a fairly large military body to try and penetrate what must have seemed to all but the natives an impenetrable wilderness, the writer does not think it would be regarded as posing a threat to the new Establishment. The 'Old Order' of Northumbria were all domiciled and exercised their influence from the eastern plains. Further to that, the preponderance of non-Norman names that stare at us from the pages of the printed medieval extents and inquests as late as the thirteenth century indicate a reasonably undisturbed area (15).

LONG ESTABLISHED CUSTOMS

The continuation until the present day of using British quarter days to govern the farming year, that is, Candlemas, Whitsuntide, Lammas and Martinmas, instead of the English norm of Ladyday, Midsummer (St. John), Michaelmas and Christmas puts Lancashire into isolation from much of England. Candlemas (Feb. 2nd) loomed large in peoples' lives; this was the day that servants commenced their year's engagement, land was entered into or given up and rents were due. Houses changed hands on May Day. On Layton Hawes stood a farm which was conveyed to Richard Watson in 1832, the premises "..in the tenure or occupation of Richard Rossall under lease or agreement of which two years were unexpired at Candlemas and May Day, 1832..."(16) A study of the 'General Views of Agriculture' made for various other parts of England shews a different arrangement. (17) The complete domination of English quarter days in the medieval accounts and extents that are in print for Lancashire make it remarkable that a system of British quarter day rents and services should have survived at grass-roots level. In any published records since the medieval period the writer is not aware of any influx of a dominant administrative class of people into this area to effect a change of system. The answer must lie in the inflexibility of the Norman clerks. Whether they were themselves Norman or not, their apprenticeship would be in the Norman Church and military households which shews in the written records with a monotonous regularity. It would be doubtful whether the authorities would shew any interest other than in the collection of the rents by the stated date of the aggreement or leases. The fact that English quarter days were some weeks later than the British ones would have allowed the two systems to operate alongside each other; one recorded in documents and the other passed on from generation to generation amongst the customs of husbandry.

It is recorded as late as the fourteenth century, just to the north of Amoundernesshire, that cowmale (or cornage, or cowscot - an ancient render of cattle later commuted to cash) was still being paid in Skerton, Overton, Over Kellet and Heysham. Some of these townships also rendered Beltanecow every third year at Michaelmas (18) (the traditional day should have been Beltane - May Day). More important for our purpose is the reference to Robert Dikkeson of Great Singleton who held a messuage and two oxgangs of land in bondage in the early fourteenth century. Amongst his services we find "....and for a certain custom of finding his portion of four cows, together with his neighbours being natives, anciently paid to the lord for the lord's stock by custom which is called cowscot....and also beyond the service and aforesaid customs of carrying victuals at each coming of the lord from Ribbell bridge into Lancaster castle and in the lord's departure unto the said bridge he shall take needful victuals for himself and his beasts...(19)

In Thornton, during the same period, and referring to certain tenants "...They hold one carve (or hide) of land in Thornton, in a place called Staynolfe (Stanah) in drengage, paying yearly five shillings at Annunciation and Michaelmas. And it is the custom for the drenches (drengs) when mowing, to have food and puture for the children of the lord and their nurse, and for the horses and dogs of the lord" (20). Likewise, on the earl of Lancaster's estates in 1346 at Stalmine, Thomas Goosnargh and Nicholas Butler were obliged to board and lodge the serjeants and their retinue and horses. In Thornton in the same extent "...it is the custom of the drengs to find meat and drink for the lord's foresters and provender for their horses and the lord's hounds..." (21) Layton had similar renders.

Typical of an area that was predominantly pastoral in economy - the climate and prevailing wind dictated that (22) the bondman of Amoundernesshire was not over- burdened with the weekly work found in champion country. Their duties consisted mainly of boon days; days given to the lord to facilitate the working of the farming year. (It is worth noting here that boon days survived into living memory at Pilling.) By the later twelfth century when surveys were becoming available to us for Lancashire, most of the services seem to have been commuted to a money rent, and the reason behind them was fast fading from folk memory. Moving on into the fourteenth century, we find that at Ribby in 1346 "...and also by ploughing, harrowing, and reaping the corn, touching whose repast or the quantity of the boon works they are altogether ignorant, rendering yearly..."(23)

To the above may be compared the lack of remembrance; again at Ribby "Of all the aforesaid lands render to the lord by ancient custom...beyond the rent and customs aforesaid, 13d, but for what, they are altogether ignorant."(24) The same problem seems to occur in Whittingham in 1324 where the clerk could not find a heading to enter the money under. These small sums which defy easy accounting also occur in the rentals for Haighton, Broughton, Bilsborrow and Elswick (25). These lost headings and ancient customs are surely the dying embers of cowscot.

PRE-CONQUEST POPULATION

The biggest stumbling block to any investigation of the state of occupancy of Amoundernesshire in early times is the Domesday Book. The vills listed in 1086 indicate the then most important settlement in each township or large estate such as Garstang. Sixteen of the vills were inhabited by a few people, but the commissioners did not know how many. The rest are waste. The present writer is of the opinion that much rests upon what was the meaning of 'waste' in this hundred and what the commissioners and their clerks thought it meant. The Oxford English Dictionary implies that 'waste' is a word of many meanings, and in the weaker sense "not applied to any purpose; not utilised for cultivation or building". (26) Not in use for cultivation might imply, particularly in a predominantly pastoral region, that it was rough grazing land. The proceedings for the Manorial Court of Pilling in 1753 make it abundantly clear that the waste of the township, known as the Moss, was regularly used for grazing, and many of the inhabitants had rights for that purpose. (27) The waste, known in the Fylde of Amoundernesshire as either Moor or Moss, depending upon location, is shewn in various records as having a value, sometimes above that of arable townfield. (28).

W.E.Kapelle (29) is of the opinion that there was no wasting of the lands of Amoundernesshire after 1066 (the harrying of the north in 1069-70) because the lands are recorded as waste before 1066; that would appear to be true if waste is accepted as meaning destroyed or unproductive, which the present writer does not. It is also Kapelle's view that Amoundernesshire may have been surveyed from no nearer than York. With regard to that opinion, which seems wholly plausible, it is perhaps worth remembering that the commissioners or their staff thought that sixteen vills had a few inhabitants. Anyone travelling between Lancaster and Preston on the main established direct route would, and still will, pass through or between sixteen townships within the boundaries of Amoundernesshire.

The number of Angles settling in the area under discussion seems, according to Kenneth Jackson, to have been numerically small. In "Studies in Early British History", after delineating sections of Britain subjected to Anglo-Saxon administration in the three waves of occupation, Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire north of the River Ribble in the middle the last being in part and third quarter of the seventh century, he goes on to say "The reason for the much greater Celticness of these regions can hardly be purely chronological, for they were settled not very much later than the second main area. It must rather be chiefly a question of relative numerical strength; the English element must have been smaller than further east."(30) With regard to the Scandinavian settlement in the area, which appears to have been peaceful and possibly could have been the result of purchase, (31) Gillian Fellows-Jenson (32) is of the opinion that more of this settlement came from over the Pennines than has hitherto been thought, and that the influx from Galloway, the Western Isles and the Isle of Man was considerably more than the settlement from Ireland, although that did occur. It is conceivable that these people from the west and north, long settled in Gaelic speaking regions and often bearing Gaelic personal names, would be familiar with the type of tenure and land division which they encountered in Amoundernesshire.

The ancient customs discussed in the preceding section would hardly have been passed down until the fourteenth century (although the memory was by then fading) without a basic parent-to-child transmission. Any drastic decimation of the area's inhabitants would have obliterated the need for these customs from the long distant past, and any later colonising replacement population would bring their own ideas with them.

CONCLUSION

The writer has endeavoured to shew in the pages above that Amoundernesshire and its component parts are the repository of ancient customs, what Gillian Fellows-Jenson referred to as the "demonstrably archaic nature of society in Lancashire" (33). The documentary facts support the still discernible evidence of the quarterland skeletal frame of the townships surviving from the days of the comital estates. The evidence is further bolstered by the existence of four principal houses in most of the lowland and non-vaccary townships in the Hundred, as shewn in the Gazetteer. All the eastern part of Amoundernesshire became the king's forest after the Conquest, and much of the lowland area came under its view as far as the forest laws were concerned. This may also have been a salient factor in the preservation of ancient ways.

The whole of the foregoing is extremely suggestive of an area passed by in the turmoil of change; in fact, W. E.Kapelle wrote "...Lancashire with the adjoining parts of Westmorland and Cumberland was a late conquest from the kingdom of Strathclyde, and the pattern of landholding that existed there in 1066 is just what one would expect to find in a recently conquered area. Arrangements were simple, and the claims of the king were still strong. Furthermore, it might be hazarded that if primitive simplicity existed anywhere in Britain in 1066 south of the highlands of Scotland, the lands of the old kingdom of Strathclyde were the place to find it." (34).

GAZETTEER (35)

THE TOWNSHIPS OF THE PLAIN. (map reference is shown by number in brackets).

BROUGHTON. (45) This consists of SHAROE, URTON, INGOLHEAD and CHURCH. The first three are regularly mentioned in seventeenth century wills as well as in medieval documents. Church appears as a hamlet in an 1851 directory, its principal house was Bank Hall, an externally unprepossessing structure, which has as its core a very impressive timber-framed cruck-truss house, possibly late medieval. Church also contains the hamlet of Lightfoot (or Lightford, or Lightwork) Houses, often a location in probate records from the seventeenth century. It is possible that there has been a shift of population in fairly recent times to nearer the church, and a name change as a result.

BARNACRE WITH BONDS. (52) The writer suggests that each is a township in its own right, having been combined at some later date.

BARNACRE appears to be made up of WOODACRE, LINGART, TURNER (G) and STIRZAKER. There is a legend, recorded by Hewitson in his 'Northwards', of the Barnacre lords who lost their rights in dubious circumstances. Thought to be four in number, they had possession of a pew each in Garstang parish church (St. Helen's, Churchtown). BONDS has BYREWORTH, HOWETH (now Calder House), DIMPLES and GREENHALGH. The title deeds of the Byreworth estate, along with those of Howeth (now Calder) House, also indicate that each had some of their land designated demesne. Dimples has a hall and Greenhalgh a fortified manor house.

BRYNING WITH KELLAMERGH. (13) This includes GREAT CARRSIDE, LITTLE CARRSIDE, KELLAMERGH and BRYNING. All are extant on the O.S.map.

BISPHAM WITH NORBRECK. (2) This is extant as WHITEHOLME, NORBRECK, LITTLE BISPHAM and GREAT BISPHAM.

CATTERALL. (29) The township is made up of RIPON, SILCOCK, ROWALL and HALECAT.

All are discernible at present except Halecat, which appears to have left no trace (Ekwall). Four miles north east of Catterall is Landskill, a detached part of the township in the fells which was probably a vaccary; the portion of the upland area which was allocated for the use of the lowland township; both were in the large pre-conquest estate of Garstang whose extent is thought to have been much as the pre-nineteenth century parish, in excess of 25,000 statute acres. Catterall Hall must have been the seigneurial base and possibly sited at Halecat.

CLAUGHTON. (51) This consists of MATSHEAD, STUBBINS, DUCKWORTH and HEIGHAM. Matshead is an ancient and important house site. Stubbins has a house, lane and Little Stubbins. Duckworth has its Hall and farm, and Heigham is discernible in the present seventeenth century Heigh House. Near to Heigh House are Infield House and Longfield House, indicating an independent townfield or arable system for that Quarter.

CLIFTON WITH SALWICK. (39) LUND, SALWICK, CLIFTON and GRACEMIRE. The first three are very obviously extant. The northern portion of the township is devoid of settlements, but has Gracemire House, an ancient estate, situated there.

CARLETON. (3) RINGTON, NORCROSS, GREAT CARLETON AND LITTLE CARLETON as extant.

CABUS. (25) CROSTON, GUBBERTHWAITE, CARRHOLME and HAGRIMAI. Croston is evident by Croston Road and Croston Barn, Gubberthwaite by Gubberford Lane and bridge and Carrholme by Carr House. The lost Hagrimai (De Hoghton deeds) may be in the area now known as Cabus Nook.

CLEVELEY. (55) A small hilly undivided township, possibly once the detached cow farm of another township, (c.f. Catterall and its relationship with Landskill).

ELSWICK. (17) There is no apparent sub-division; the village has a tradition of having been a commercial centre and it is very obvious that it was planned on a burgage plot system.

FULWOOD. (44) FULWOOD, CADLEY, KILLINSOUGH and HYDE. Fulwood and Cadley are now suburbs of Preston; Killinsough remains as a farm name. Hyde (and Hyde Park; Ekwall) seems to have left no trace, although in 1342 a William, son of Henry de Hyde occurs in the De Hoghton deeds.

FISHWICK. (42) A small township with only two apparent divisions, FRENCHWOOD and FISHWICK, both within the urban sprawl of Preston. Possibly further investigation could shew 'Great' and 'Little' divisions of both of these.

FRECKLETON. (37) There are three important dwellings within the township, Higher House, Lower House and Raker House. In addition, there is the hamlet of Hall Cross, which suggests that formerly a cross stood near to a now demolished Freckleton Hall in that vicinity.

FORTON. (56) There are four areas in this township where the field pattern as shewn on the 1.25000 0.S. map indicate former strip ploughing and therefore the former existence of townfields. Area one is centred around Forton Hall, Raingills and Goose Green. Area two stretches between Clifton House, Killcrash and Norbreck House. Area three starts at the district known as Potters Brook and centres on the whole length of Wallace Lane. Finally, the fourth area is situated in the Moorhead and Hollins Lane part of the township. Naming the parts remains elusive.

GRIMSARGH WITH BROCKHOLES. (62) HAYLEY, RED SCAR, BROCKHOLES and GRIMSARGH. The now lost Hayley occurs in the thirteenth century (De Hoghton deeds) as does Red Scar, now an industrial estate, but known then as Raschagh. Grimsargh is a village to the north east of Red Scar and the Brockholes lie to the south west.

GREENHALGH WITH THISTLETON. (16) CORNAH, ESPRICK, THISTLETON and GREENHALGH are all extant.

GREAT ECCLESTON. (30) LECKONBY, RAIKES, COPP and ECCLESTON. Leckonby House is at the north west of the township, Raikes Hall at the north east, Copp in the south west, and Great Eccleston Hall in the south east.

HARDHORN WITH NEWTON. (6) STAINING, NEWTON, TODDERSTAFFE and HARDHORN. Todderstaffe, Newton and Staining have. a Hall each, but Hardhorn does not shew signs of a principal house, although it had a market charter granted in 1348 (36) by Stanlaw Abbey and one could envisage a resident official. There is also an (36) I called Dover close to Staining Hall which may have been the lord's demesne, Staining being the major part of the township according to the Domesday Book (c.f.Lewth in Woodplumpton).

HAMBLETON. (Hamilton) (20) TOULBRICK, CROMBLEHOLME, BICKERSTAFFE and SOWER CARR are all extant.

INSKIP WITH SOWERBY. (31) INSKIP, SOWERBY, CROSSMOOR AND MORLEY (MORILLY). The first three are extant and well represented in the St. Michaels-on-Wyre parish registers over the centuries, as is Morley. There was a Morley Hall until about thirty years ago. Latus (Latewyse, Lewtas, Lewty) Hall in the township probably takes its name from the family occupying its estate (c.f.Ambrose Hall, Woodplumpton.)

KIRKLAND. (27) HUMBLESCOUGH, GARSTANG MARKET TOWN, GARSTANG CHURCH TOWN and KIRKLAND. Humbles cough stretches all along the western edge of the township; the name is present in the farm and the wood. In 1620, James Stirzaker, yeoman, describes himself in his will as "..of Humblescough". Garstang Market Town and Garstang Church Town occupy the north east and south east part of the township respectively. Kirkland Hall dominates the central portion.

LEA, ASHTON, INGOL and COTTAM. (40) Lea and Cottam have a Hall each, and Ashton has its principal house, Tulketh Hall. Tanterton Hall is within Ingol and was perhaps its principal abode. In addition to Tulketh and Tanterton, the township includes English Lea, French Lea, Westleigh and Sidgreaves (or Greaves).

LAYTON WITH WARBRECK. (5) GREAT LAYTON, LITTLE LAYTON, WARBRECK AND WHINNEY HEYS. The first three are still extant on maps of Blackpool. The seemingly vacant part of the township as seen on old maps was occupied by Whinney Heys Hall, which had some of its land designated demesne.

LYTHAM. (11) EASTHAM (Eastholme), BIRKS (Bircholm), MYTHOP and KILGRIMOL. Eastham and Birks are still to be located as names on the map. Mythop is now to be found only as the name of an avenue in Lytham. Kilgrimol is well documented (Ekwall, Fishwick) and lives on in local legend.

LITTLE ECCLESTON WITH LARBRECK. (18) LITTLE ECCLESTON, LARBRECK, THE WALL and GILLOW. The first two have a hall each, and the title deeds of Little Eccleston Hall refer to The Wall being held for part of a knights fee ("John Wilkinson ...also held the Half-hey in the Wall of the King"..V.C.H.). The north east part of the township once contained Gillow House, home of the Gillow family who achieved later fame in the design and manufacture of furniture; Fishwick refers to William Gillow of Gillow in Little Eccleston.

MYERSCOUGH. (32) STANZAKER, MIDGEHALGH, BADSBERRY and ASHBY. Ashby was in the Domesday Book but it is usually now claimed that it is 'lost'. The present writer suspects that it was the area round the present Myerscough Lodge, known often in seventeenth century wills as 'Lodge in Myerscough'. In that part of the township are to be found two farms named Nearer and Further Light Ash and the tantalizingly named Ashby's Farm. Stanzaker has its Hall, Midgehalgh Hall is now known as Midge Hall, and Badsberry is presently called Fence Foot.

MARTON. (8) GREAT MARTON, LITTLE MARTON, PEEL and REVOE. All four are to be found on present day maps. Peel is possibly the later name for Linholm, now a 'lost' place. Ekwall suggests Linholm means the island where flax is grown, and Peel is a virtual island in the mossland, away from the main higher land of the township. Revoe became a single farmstead and now a district of central Blackpool. Many older Blackpudlians declare their Revoe origins with pride. There were twelve contiguous fields in Revoe which bore that name. There was also a Revoe field in the adjacent township of Layton where the two met.

MEDLAR WITH WESHAM. (15) BRADKIRK, WESHAM, MOWBRECK and MEDLAR, each with a Hall - all are extant.

NEWTON WITH SCALES. (38) NEWTON, SCALES, DOWBRIDGE and THE MOOR. The first three are still extant. A void in the township to their eastern side contained the recently demolished Moor Hall, and in 1323 (De Hoghton deeds) the hamlet of Le More contained eight cottages and the hamlet of Le Skales is also mentioned.

NATEBY. 26) KILCRASH, FORD GREEN, NATEBY and LITTLE NATEBY. The first three are to be found on the O.S. maps and Bowers House is in Little Nateby.

PREESALL WITH HACKENSALL. (22) PREESALL, HACKENSALL, AGLEBY and LICKOW. The west slope of Preesall Hill shews signs of strip farming below the hamlet and also has a Great Meadow on the flat land adjoining. Hackensall Hall's surrounding fields are large but have the shape and layout suggestive of previous strip ploughing. The area around the now demolished Agleby's Farm has traditionally shaped long fields with curved sides. Lickow shews strip-like field divisions and has a divided Great Field. The present hamlet of Preesall Park has similar type fields which link up to Lickow, which suggests that they all belong together.

PILLING. (23) SMALLWOOD HEY, DAMSIDE, MOSSHOUSES and SCRONKEY (Skronkall) are all to be found today and appear on the 1746 map of Pilling. The township has four principal houses, Pilling Hall, Brick House, Pasture House and Carr House. All but Pasture House appear to have been moated. The four hamlets surround the irregularly shaped townfield area, but it is unclear which principal house had the overview of which hamlet.

THE RAWCLIFFES:-

UPPER RAWCLIFFE WITH TARNACRE. (28) WYRE, TURNOVER, TARNACRE and ST.MICHAELS (ON WYRE). All four have a principal residence called a Hall. The township also contains White Hall, formerly known as Upper Rawcliffe Hall, which possibly was the seigneurial base.

MIDDLE RAWCLIFFE. (Now incorporated into Out Rawcliffe) (19) STONECHECK, SKITHAM (Scytholm), HOSKINSHIRE and ASHTON are all extant as names on the map. The present Rawcliffe Hall would be the seigneurial centre.

OUT RAWCLIFFE. LISCOE, HALE (Nook), MOORHAM (Moreholm), and DOCKINSALL are on the modern maps, some, as is often the case, surviving as a farm name only; the need for attendant houses having been eroded by shifts in agrarian practice. The previous house on the site of Quaker's Farm at Town End, which had a late medieval core, would probably have been the principal seat of administration.

RIBBY WITH REA. (14) COMPTON, HILLOCK, WREA (Green) and RIBBY (Rigby). Wrea Green and Ribby are well known in the district. Compton has disappeared but is well documented. It was for some time held by the Shaw family, one of whom was the Lancashire historian R. Cunliffe Shaw. Hillock is the part of the township that runs as a spur between the northern parts of Warton and Freckleton. Further Hillock Farm was a moated site.

RIBBLETON. (43) HOLME SLACK, FARINGDON, SCALES and HAUGHTON. Holme Slack is still an identifiable district in this now built-up township. Faringdon Hall was there in 1851 and the now 'lost' Scales existed in 1252 (Ekwall). A Shireburne family will of 1581 refers to lands in Haughton in Ribbleton (The Shireburnes were lords of the manor). The name seems now to have disappeared.

STALMINE WITH STAYNALL. (21) WARDLEYS, CORCAS, STAYNALL and STALMINE. Wardleys is an old port on the river Wyre which deteriorated from the beginning of the nineteenth century onwards. Corcas is now only the name of a lane but occurs as the name of a place in documents of 1220 (Ekwall). Staynall and Stalmine remain as communities today.

SINGLETON. (7) GREAT SINGLETON, LITTLE SINGLETON, NEWBIGGIN and SUMMERER. Newbiggin is now known as Singleton Grange. Summerer appears as a score of field names around the present Summerer Farm, perhaps the extent of the Quarter's own Small townfield. The names of Brackenscales and Avenham, in Singleton but on its extremities, are clearly assarts.

THORNTON. (1) ROSSALL, BURN, STANAH and LITTLE THORNTON. Little Thornton, Burn and Rossall have halls, and Stanah has Stanah House. The minor names of Trunnah and Holmes are recorded in medieval times, and Ritheram in the late sixteenth century, but what significance they held in the past is uncertain.

THORNLEY WITH WHEATLEY. (60) BRADLEY, STUDLEY, THORNLEY and WHEATLEY. All are mentioned from the thirteenth century. Bradley and Thornley Halls are extant, and Wheatley Farm house of the early eighteenth century looks too important not to have had the status of House at least. Of Studley, there now seems to be no trace.

WOODPLUMPTON. (34) PLUMPTON, CATFORTH, CHARNLEY EAVES and BARTLE, all are so named on the Tythe Award Map of 1838. Henry Threlfall, yeoman, in his will of 1694 describes himself as of "Plumpton Quarter within Woodplumpton". Seventeenth century wills are usually very specific in describing where in Woodplumpton the deceased had resided. The township is sufficiently extensive for each hamlet to have had its own townfield and the areas shew up well on the Tythe Award Map. There is also within Woodplumpton a settlement called Lewth; this is part of Charnley Eaves and was formerly the lord's demesne of the township (PRO SP/160 No.4049 fo.540).

WINMARLEIGH. (24) The township has a plethora of houses designated 'Hall'. There are Gibstick Hall, Sharples Hall, Tyrer Hall (now demolished) and Gift Hall as well as Winmarleigh Old Hall. It is possible that an arrangement similar to that of the adjoining township of Pilling appertained, but with a seigneurial residence in addition.

WEETON WITH PREESE. (9) MYTHOP, PREESE, SWARBRICK and WEETON. The first three have a Hall, and the site of Weeton Hall is presumably Hall Hill above Weeton village.

WESTBY WITH PLUMPTONS. (10) GREAT PLUMPTON, LITTLE PLUMPTON, WESTBY and BALLAM are all extant.

WHARLES, TREALES AND ROSEACRE. (33) SASWICK, ROSEACRE, TREALES and WHARLES. The three hamlets that give the township its name are extant, but leave a large empty area at the north west corner of the township. This empty area is dominated by Saswick House.

WHITTINGHAM. (47) CHINGLE, ASHLEY, CUMERAGH (Cumberhalgh) and DEAN are names that are all to be found on the present day maps and occur in the De Hoghton deeds.

WARTON. (12) COWBURN (Cowburgh), BRAMPLANDS, BARBARICK (37) and WARTON. The chartulary of Lytham Priory mentions a ford between Estholme (in Lytham) and Cowburgh. The north eastern portion of the township has a 25 acre group of fields containing the name Barbarick, (37) whilst in the south western corner a group having the name Bramplands extends to some 32 acres. The south west is the area of Warton Bank and Bankhouses. A sixteenth century tythe ledger of Vale Royal Abbey lists "...Warton, Bankhouse et Conoburn. 511 6s. 8d." (Fishwick's History of Kirkham).

The above townships do not include Poulton and Kirkham. Both these places were granted, prior to 1066, by Roger of Poitou to priories and appear to fall outside the general run of agriculturally biased townships. According to the codified Welsh laws in the book of Iorwerth (38), each Hundred had four extra townships which were the king's demesne. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that Kirkham and Poulton were in origin king's demesne, Kirkland and Preston being the other two. Hypothetical though the idea may be, it leads the writer to suggest that the fee simple of the three Amoundernesshire churches that belonged to the capital township of Preston, as indicated in the Domesday Book, relate to Kirkham, Poulton and Garstang (which is situated in Kirkland).

The writer is of the opinion that the remaining fifteen townships of the Wapentake, Alston, Barton, Haighton, Elston, Aighton (with Bailey and Chaigley) Bleasdale, Bowland (with Leagram), Chipping, Dutton, Ribchester, Dilworth, Alston (with Hothersall) Bilsborrow, Nether Wyresdale and Goosnargh, were basically upland pasture and vaccary, considered as an adjunct to the ancient estates of the plain. The Quarters apparent in the Fylde plain of Amoundernesshire are not to be found in these uplands, and the only links that can be made at present between the upland and lowland are:- Kirkham with Goosnargh, Garstang with Nether Wyresdale and Bilsborrow, and possibly St. Michaels-on-Wyre with Aighton, Bailey and Chaigley (39).

REFERENCES

1. See the Oxford English Dictionary.

2. A township. See also "Men of the North", R. Cunliffe Shaw (Preston n.d.).

3. "North Wales", G.R.J. Jones, p.430, quoting 'Llyfr Iorwerth' (The Book of Iorwerth) D.Jenkins, Ed. 1960, in 'Studies of the Field Systems of The British Isles', Eds. A.R.H.Baker & R.A. Butlin. (Cambridge University

Press, 1973).

4. "Carlisle And The Kingdoms of The North West", R. Cunliffe Shaw (Guardian Press, Preston, 1963); a search of all the D.B.Cheshire manors which ad- join the above found no comparative dues.

5. 'North Wales', op. cit., p 441.

6. 'Cockersand Chartulary', (Chetham Society, 1898-1909).

7. 'The De Hoghton Deeds & Papers', J. H. Lumby, (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1936)

8. The Tythe Award Map for Woodplumpton, 1838. Lancs. Record Office.

9. 'Northwards', Hewitson (Guardian Press, Preston, 1900).

10. 'A History, Directory and Gazetteer of the County Palatine of Lancaster' Edward Baines, (Liverpool, 1824). p 12.

11. The Norman Conquest of the North', William E.Kapelle, (Croom Helme. London, 1979).

12. Ibid. See the conclusion.

13. In 'Celt & Saxon; Studies in the Early British Border' Ed. Nora K. Chadwick (Cambridge University Press, 1964). See also 'Peat and the Past', Howard-Davis, Stocks & Innes, Lancaster University 1988 p 2, 1.3 An Historical Perspective.

14. The House and Farm Accounts of the Shuttleworths, 1582-1621 (Chetham Soc.)

15. University of Lancaster C.N.W.R.5. Regional Bulletin "The Fylde in its setting" R.C.W. No.8, 1994.

16. "A History of Leagram", J. Weld, (Chetham Society, 1913). 'A General View of Agriculture of the County of Lancaster', J. Holt, 1975. 'The Great Diurnal of Nicholas Blundell, F.Tyrer, 3 vols. (Record Soc. of Lancashire & Cheshire, 1972). All give numerous examples of Candlemas being the important day for the rural community in Lancashire. The coastal part of Cumbria was still paying rents in part at Candlemas in 1969, although other influences were creeping in and Lady Day had been established on some farms. "The Sociology of an English Village; Gosforth", W. M. Williams Routledge & Keegan Paul Ltd. (London, 1969). For the hillier parts, Mr. Clifford Clarke of Far Orrest, Applethwaite Common, informs me that rent day is at Martinmas (A British quarter day, although the land is entered on May Day). Dr.J.R.Minto, 0.B.E. of Bridge of Weir informs me that the British quarter days cover all aspects of Scottish life and the coastal plain in south west Scotland uses Candlemas and the uplands, Martinmas for the principal rent day. For some reason the Isle of Man does not, as one would expect, follow the same pattern; Manx quarter days are Feb. 12th., May 12th., August 12th. and Nov. 12th., the last being the letting and rent day, which is also the day after Martinmas (Nov. 11th.) the day which is used in Westmorland (Communication from Mr. Nigel Wright of the Manx Museum). In north Wales, from the recollection of some of the partners of Messrs. Jones Peckover of Abergele, land agents and surveyors since 1880, the English quarter days are used, March 25th. and Sept. 29th. being the usual ones.

17. A General View of Agriculture for the County of Lincolnshire', Arthur Young (1813), p 47 & pp 445-6, Ibid. for Suffolk, (1813) p 224, Ibid. for Sussex, (1813) p 407, Ibid. for Hertfordshire (1804), Ibid. for Oxford- shire (1813), and also 'Elizabethan Life: Disorder', F.G.Emmison, (Essex County Council, 1970), pp 83 & 127.

18. 'Lancashire Inquests, Extents & Feudal Aids', 3 vols., W. Farrer (Record Society of Lancashire & Cheshire, (1903 - 15).

19. Ibid. vol. III, p 126, see also 'Men of the North', op. cit., pp 177-8.

20. 'Three Lancashire Documents of the Fourteenth & Fifteenth Centuries', vol. 11, De Lacy Survey of 1320-1346, (Chetham Society, 1868)

21. 'Lancashire Inquests etc., op. cit. vol. III, pp 112 & 115.

22. 'The Agricultural Revolution', Eric Kerridge, (Augustus M. Kelly, New York, 1968), (Allen & Unwin, London, 1967), and 'Studies in the Field Systems of the British Isles', op. cit.

23. 'Lancashire Inquests etc.,', op. cit.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Oxford English Dictionary.

27. From some mid-eighteenth century proceedings of Pilling Manor Court loaned to the author and now in transit to the Lancashire Record Office.

28. From 'South Lancashire in the Reign of Edward III' (Ed. G.H. Tupling, Chetham Society, 1949), we find that c.1320, Richard le Chapman of Rainford, who had been hanged for a felony, had chattels worth 10s., land to the value of 5s. 4d. yearly, and his waste was worth 6s. 8d. yearly. 'The Lancashire Inquests etc.' (op.cit) record that on the earl of Lancaster's estates, William de Twenge held amongst other lands "..a plot of Waste called Solam (Sullom) in Garstang (at Barnacre) worth yearly 6d. All of which indicates that the Waste (or Moor or Moss) in a Lancashire township had a value, sometimes in excess of arable land. See also the will of Henry Browne, Ashton on Ribble, 1679.

29. 'The Norman Conquest of the North', op. cit.

30. The British Language During the Period of the English Settlements', Kenneth Jackson in 'Studies of Early British History, Ed. Nora K. Chadwick (Cambridge University Press, 1954).

31. This would be no innovatory action. Angus Winchester in 'Landscape & Society in Medieval Cumbria' (John Donald, Edinburgh, 1987) makes reference to the purchase of estates by the Norse, and from P.H. Sawyer in 'The Age of the Vikings' (2nd. edit. London, 1971) quoted by Gillian Fellows-Jenson in 'Scandinavian Settlement Names in the North West' (C.A.Reitzels-Forlag, Copenhagen, 1985) "...King Athelstan granted Amounderness to Archbishop Wulfstan and the Church of York 'with no little money of my own' ".

32. Scandinavian Settlement Names etc. op. cit.

33. Ibid.

34. The Norman Conquest of the North', op. cit. 35. Much of the Gazetteer is from the author's personal knowledge of the area, acquired over more than six decades of exploring it and living in various parts of it. Further information has been gleaned over the years from many sources, including: -

The Place Names of Lancashire', Eilert Ekwall, (University of Manchester 1922); 'The Genealogists Atlas of Lancashire', J.P.Smith, (Henry Young & Sons, Liverpool, 1930); 'Field Names of Amounderness Hundred', F.T. Wainwright in 'Scandinavian England', Ed. H. Finberg, (Phillimore, 1975) The Parish Registers and the publications of the Parish Register Society for various dates, including Goosnargh, Garstang, Stalmine, Pilling, Woodplumpton, St.Michaels-on-Wyre, etc.; Lancashire Inquests, Extents The Tythe Award Maps of Freckleton (1838), Warton (1838), Woodplumpton & Feudal Aids', 3 vols., W. Farrer (Record Soc. of Lancashire & Cheshire); (1838), Goosnargh with Newsham (1849), Preesall with Hackensall (1839), etc.; Royalist Composition Papers in the Public Record Office, London, shire Record Office, Bow Lane, Preston (WRW/A, MF1/3, and MF1/4); (SP 23/160 No.4049 fo.540); Wills and probate inventories in the Lanca- The History, Topography & Directory of Westmorland and of the Hundreds of Lonsdale & Amounderness in Lancashire', (Mannex & Co. Beverly, 1851);

The first one inch Ordnance Survey Map, (1847) (reprint by David & Charles, Newton Abbot, sheets 15 & 20), and later Ordnance Survey Maps; Henry Fishwick's various parish histories of Amoundernesshire, (Chetham Society, various dates); 'The De Hoghton Deeds and Papers', J.H. Lumby. (Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, 1936).

36. In 'Victoria County History of Lancashire' and 'Markets and Fairs in Medieval Lancashire', G.H. Tupling; in 'Historical Essays in Honour of James Tait', (Manchester 1933). The granting of a market charter and regularising of the activities on the site by the then civic authority, was probably the reason for Hardhorn's remodelling.

37. Barbarick; This could be a description of back-breaking land, but equally well a corruption of some obscure word; F.T. Wainwright lists it with the 'breck' endings of names (Scandinavian England, op. cit.).

38. 'North Wales', op. cit.

39, Lancashire Local Historian, 1995. Bowland, as an Adjunct to the Coastal Plains of Amoundernesshire. R.C.W.

40. I am greatly indebted to Mrs. M.E. McClintock and (the late) Prof.M.W. Barley for many helpful suggestions in the compilation of this paper, but all errors and opinions are my own responsibility. My thanks are also due to Mr. Oliver Westall for kindly pointing me in the direction of some new publications which have proved most instructive.