THE PILLING MOSS ENIGMA

By John Salisbury

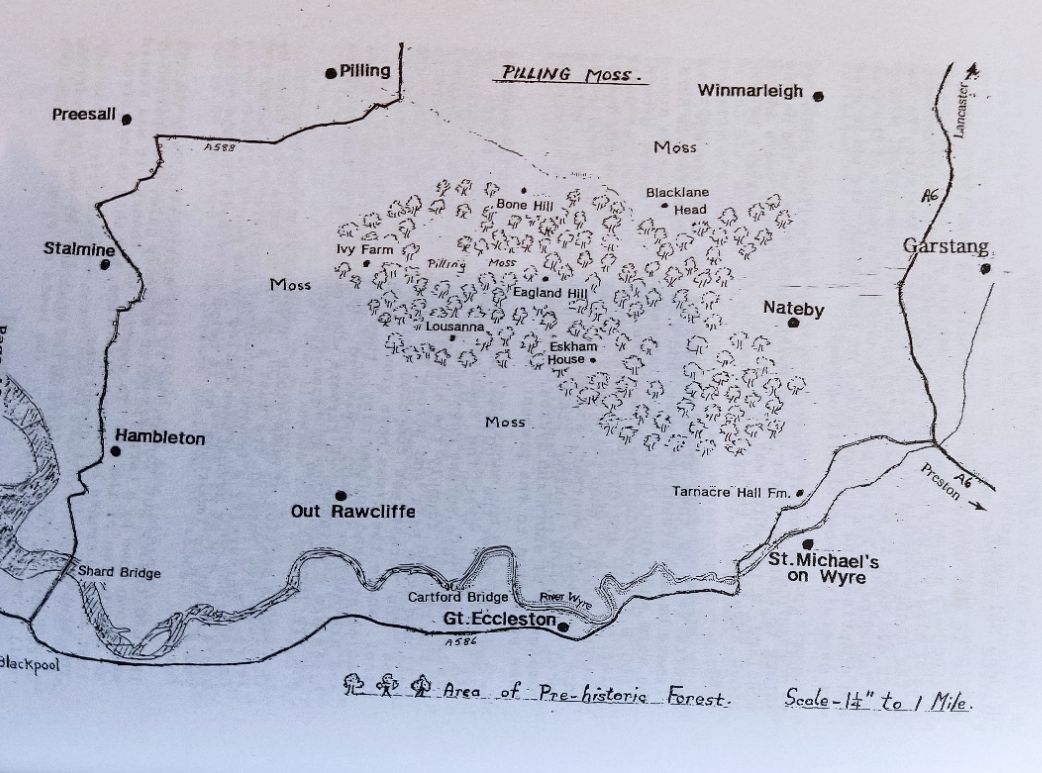

Before it was drained at the beginning of the 19th century, Pilling Moss was an extensive and desolate peat bog, covering an area of almost 9,000 acres, and was bordered to the north and west by the higher ground near Pilling village and Stalmine. To the south and east it met the rising ground of Winmarleigh, Nateby and Tarnacre. As Pilling parish was near to the centre of the area and comprised the largest extent of the region, the whole area was generally known as Pilling Moss.

In 1941, at the age of fourteen, I left the village school at Nateby to start my first job at Eskham House Farm on the nearby mossland, a job which was to last for over twenty years and to prove invaluable to my understanding of the history of the area.

Experts tell us that after the end of the last ice age, the climate became steadily warmer, and a forest began to grow here. The warm and rather humid temperatures of the centuries around 4,000 B.C. provided the ideal conditions for forest growth. Later, cooler and drier climates seem to have existed until around 1,400 B.C. when there was a gradual decline towards damper more changeable weather, and which by 800 B.C. had resulted in local flooding taking place, with bogs forming. With a complexity of short run cycles, this weather pattern has more or less persisted to the present day.

It was only after the 'bog moss' had been drained and the peat dug off for fuel, that the remains of the ancient forest was discovered. This forest covered a large extent of the southeast of the region, roughly the area around Lousanna Farm, Eagland Hill and Bone Hill and across to Eskham, Nateby and Tarnacre Moss. The forest was composed mainly of oak, yew, alder and hazel. Where the trees have grown on the 'ravin' (a mixture of glacial silt and boulder clay), they are almost entirely of oak, and are extremely well preserved. The buried remains of these trees are a nuisance to farmers when ploughing is taking place and are locally known as 'moss-stocks'.

In 1990, a section of moss-stock recovered from the forest floor level at Ivy Farm on the west side of the moss, was dated by Belfast University's Dendrochronology Laboratory as being 400 years old, and as having been felled in the year 3,023 B.C. +/-9 years. This is important, as it helps us to date the age of the forest.

The old theory put forward as to its destruction, was that it was blown down by a terrific north-westerly gale, accompanied by an inundation of the sea. To support the theory, it was stated that all the trunks lay in one direction, but this is not correct. The trunks lie in all directions.

After working for many years on the mossland, my own observations tell a very different story. The roots or stumps of these oak trees are all found upright in the exact positions where they grew; the bare trunks belonging to the roots are found lying a short distance away, and in almost every instance, the trunks have been severed from the roots at a point roughly between knee and waist high from the forest floor. In a naturally occurring situation, only rarely do trees blow down or break off in this manner, leaving the root in place. On almost every occasion, the root will be pulled up as the tree falls over. This suggests that they must have been felled in some way.

Over the years I have helped to remove large numbers of these roots and trunks, but there is an enigma here. In every instance, all the branches, large and small, are missing, as were the tops of the trunks, and yet, perfectly preserved twigs could be seen scattered around in the peaty soil. In some areas, the roots are found intact, but all the trunks are missing! We can only assume the timber must have been removed at the time the forest was being destroyed.

Recent evidence derived from pollen found on mosslands through- out Britain indicates a phase in which the forests of neolithic times were being cleared to make way for pasture land. It is said the downlands of Wiltshire were forest until cleared by neo- lithic man. Areas of East Anglia were also cleared and much nearer to our own Fylde area, the coastal plain of south west Cumbria was also permanently cleared. It is almost certain this is what took place on Pilling Moss. Neolithic earthworks have recently been discovered at Nateby, on what would have been at the time, the edge of the forest.

It seems almost incredible to us that these early farmers, using only flint and stone axes could have cleared large areas of forest but there is no doubt that this is what happened as is evidenced by the number of stone and flint axes which have been discovered here, and are still found from time to time whenever ploughing or draining operations are taking place.

Experiments have been carried out in recent years in Denmark using flint and polished stone axes, and the general conclusions were that on some woods they were almost as efficient as metal implements. The effect these early tools would have had on harder woods, such as oak, would have been much more difficult to achieve. I have heard mossland farmers describe how, when first uncovered, these felled oak trees looked as though they have almost been chewed through! This 'chewed' effect would almost certainly have occurred as an oak tree was being felled - or rather hacked down, using a flint or stone axe.

In 1869, the Rev. J. D. Bannister who was vicar of Pilling at that time, and a keen local historian, wrote of his observations of Pilling Moss, and he seems to have noticed the same 'chewed' appearance of the trees. He wrote:-

The nucleus of this extensive Moss is no doubt the debris of an ancient forest, on the destruction of the forest arose the bog. The trees that constituted the ancient forest are now generally lying in a horizontal position on the original soil and the roots are in the very place where they originally grew. I have anxiously enquired for any remains of the Beaver, thinking this animal might have been instrumental in the destruction of the ancient forest, but hitherto have met with no trace of it.'

Once the pioneering work of felling the trees had been completed it would be but a short step to turn the land into moorland pasture, with herds of cattle no doubt grazing amongst the remains of the roots and trunks. As the years passed, the remains of the oak trees must have gradually 'seasoned' in the dry climate, with the wood becoming very tough and hard, thus ensuring their preservation.

Eventually, herbage and debris seems to have started to build up at an ever increasing rate, and so burying the remains of the trees. The accumulation of these deposits has continued the preservation. This is due to a number of factors:-

The acidity or sour nature of the matrix, along with various other elements provided antiseptic properties. The moss stocks owe their colour, ranging from dark green to black to being impregnated with these elements. After the forest was destroyed, the climate must have remained dry. I say this because the fallen vegetation covering the moss stocks has tended to rot away almost to soil instead of forming peat; this would be due to the access of oxygen into the spongy, dry surface. In contrast, true peat requires almost continuous wet conditions which seals the fallen layers of vegetation permanently to the exclusion of oxygen. This prevents the complete rotting away of the material and is why peat can build up so quickly. It was not until the centuries around 800 B.C. that local freshwater flooding began to take place, thus creating the bog.